Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

(If the slides don’t work, you can still use any direct links to recordings.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Dual Process Theories

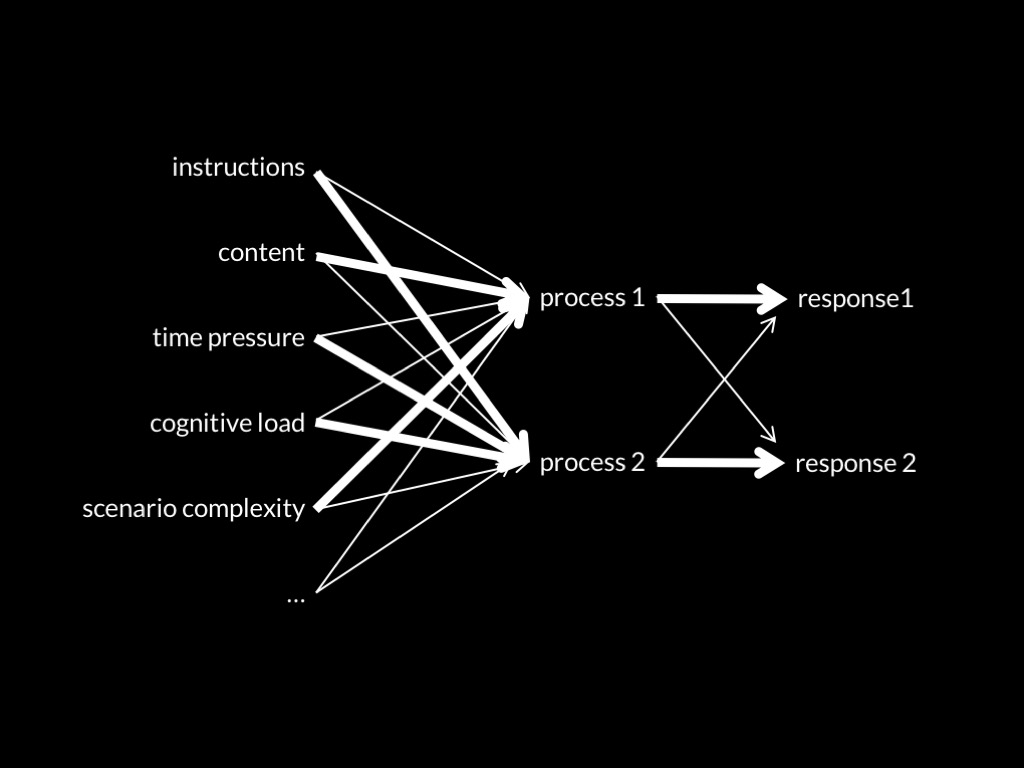

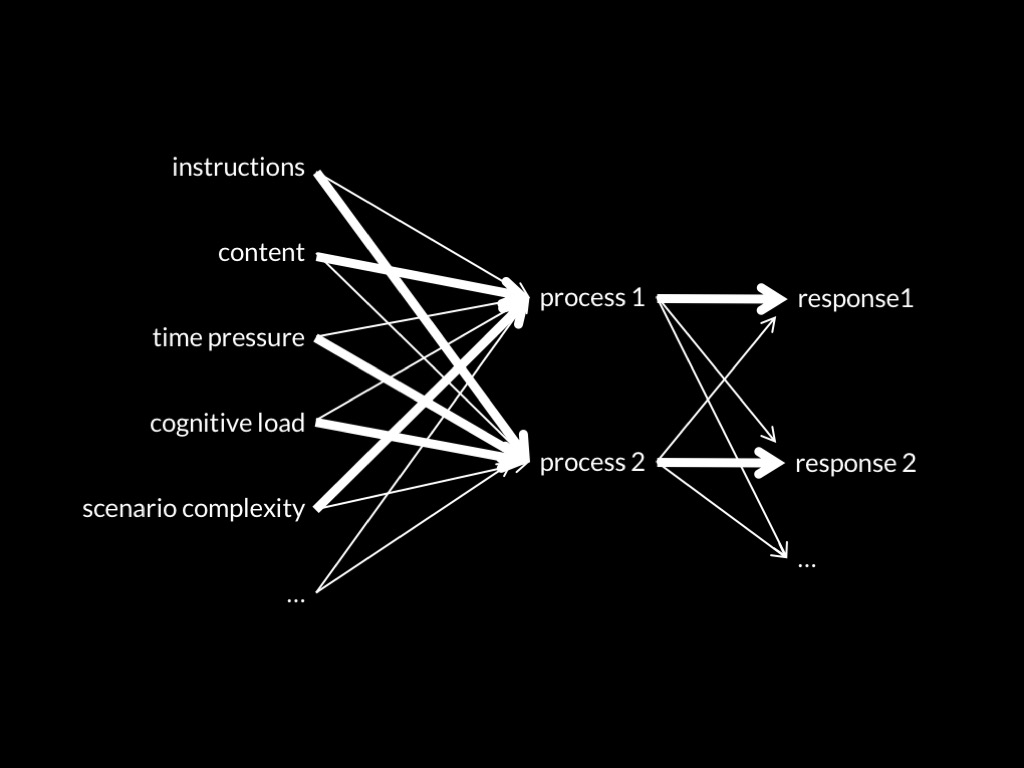

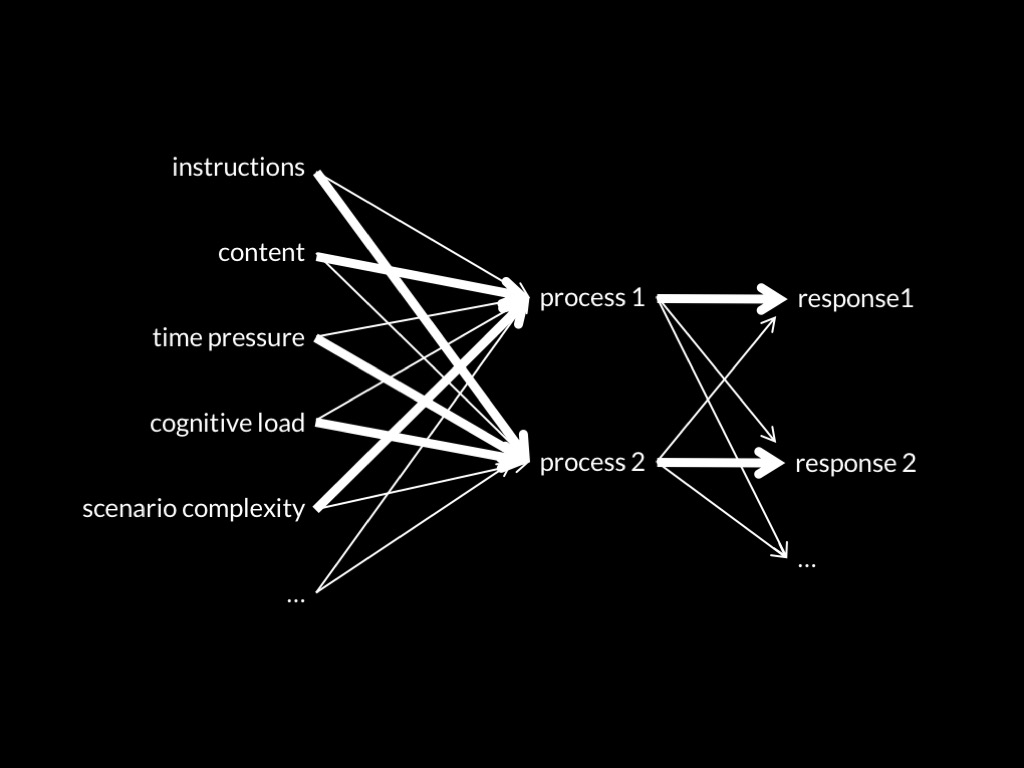

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

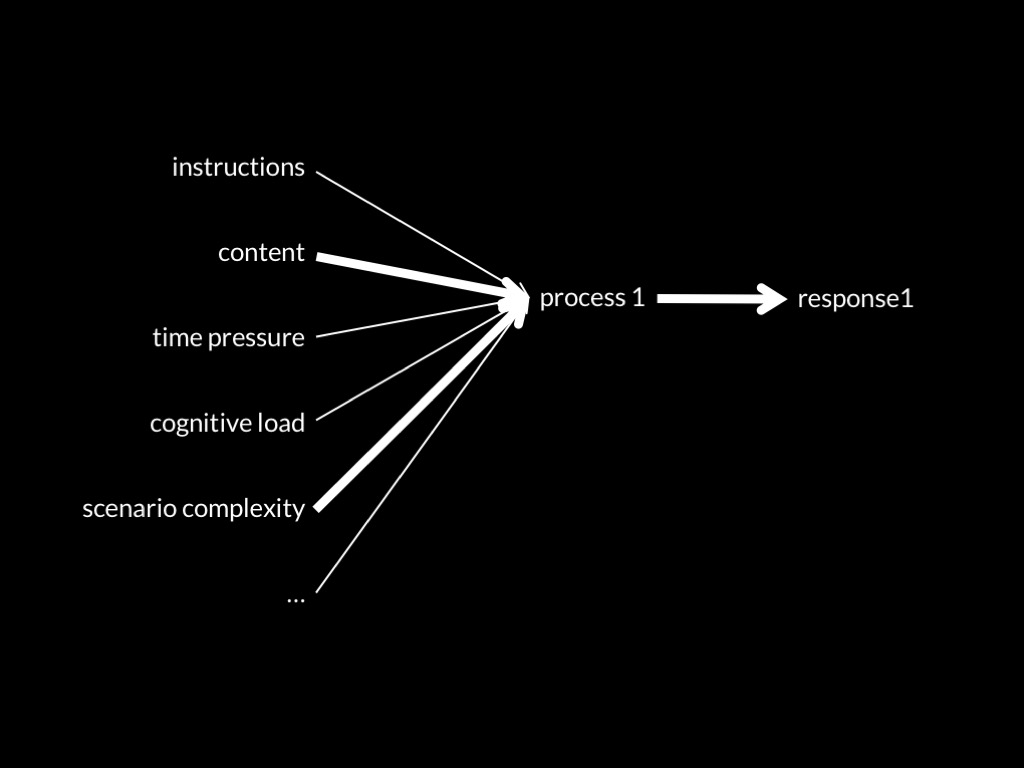

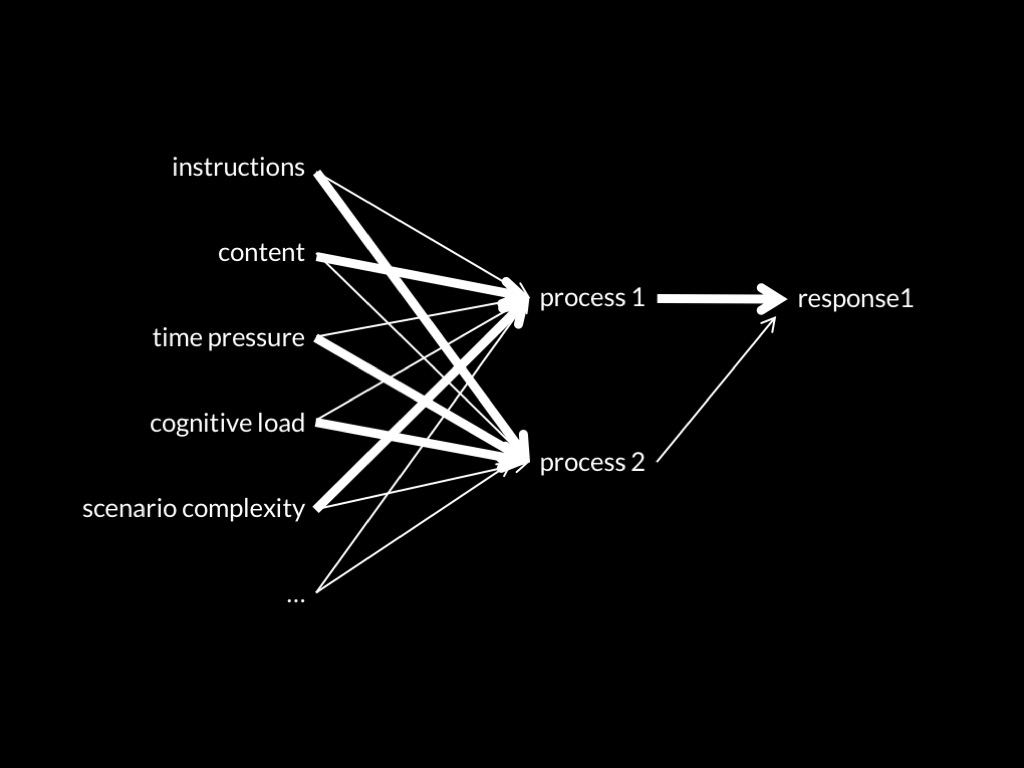

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

Answer the dilemma (see handout)

Terminology

‘consequentialist response’ = yes, kill one of your fellow hostages

Additional assumptions

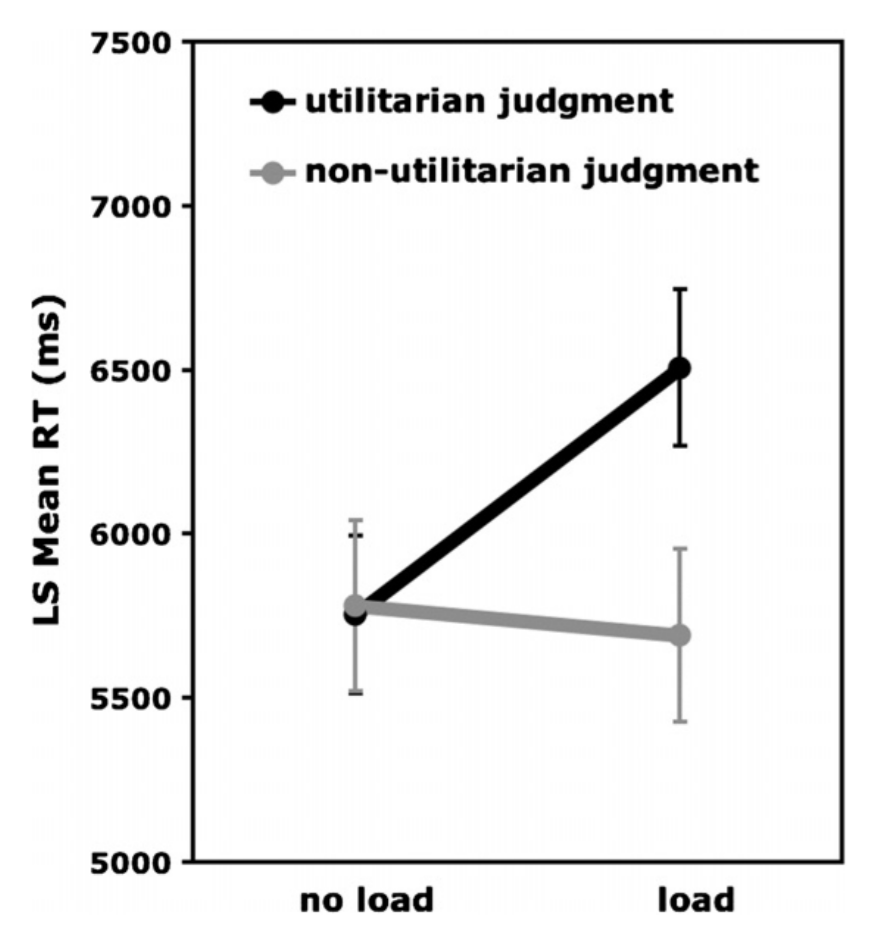

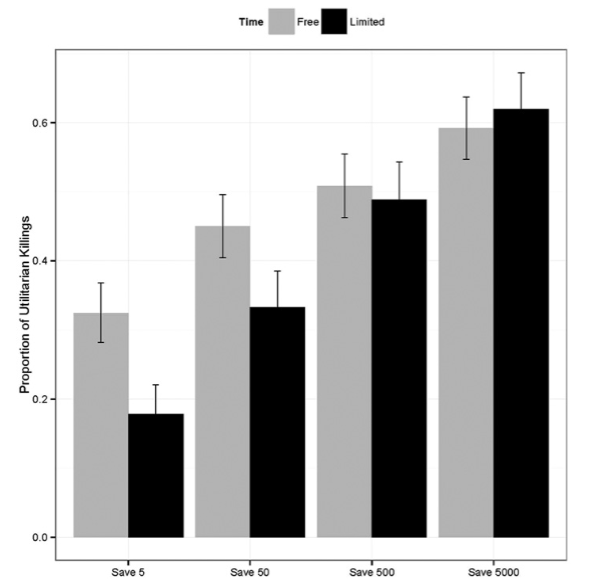

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

The slow process is responsible for consequentialist responses; the fast for other responses.

Prediction: Increasing cognitive load will selectively slow consequentialist responses

Greene et al 2008, figure 1

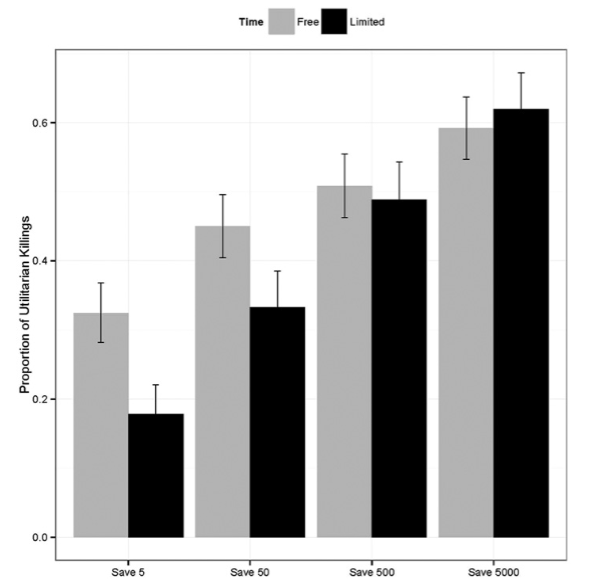

Additional assumptions

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

The slow process is responsible for consequentialist responses; the fast for other responses.

Prediction: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce consequentialist responses.

Trémolière and Bonnefon, 2014 figure 4

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.