Moral Foundations Theory: An Approach to Cultural Variation

Moral Foundations Theory is ‘a systematic theory of morality, explaining its origins, development, and cultural variations’ (Graham et al., 2011, p. 368). It comprises four assertions about the cultural origins of ethical abilities. By the end of this section you should understand, at least roughly, what Moral Foundations Theory claims.

If the slides are not working, or you prefer them full screen, please try this link.

Essay Question

This section is relevant for answering the following question:

Notes

Why This Theory?

Moral Foundations Theory is the most difficult theory to understand that we will encounter.

As we will see later, much of the evidence for key applications of Moral Foundations Theory is at best quite weak (Davis et al., 2016; Doğruyol, Alper, & Yilmaz, 2019; Kivikangas, Fernández-Castilla, Järvelä, Ravaja, & Lönnqvist, 2021). These weaknesses have recently led to the development of new and improved ways to study moral foundations across different groups (Atari et al., 2023). Applications of Moral Foundations Theory also faces significant theoretical objections (we have already seen one objection in Moral Disengagement: Significance).

We must therefore treat claims about moral foundations with caution: objections to the earlier work are now widely recognized.

So why consider Moral Foundations Theory at all? Some of its strongest opponents make the best case for studying it:

‘It would be difficult to overestimate the influence of this theory on psychological science because it caused a dramatic broadening in conceptualization of morality beyond narrow Western notions that have focused on individualistic virtues associated with protecting one’s rights—especially prevention of harm (Gilligan, 1982) and unjust treatment (Kohlberg, 1969).

‘The expansion of morality psychology to more collectivistic domains has led to substantial research into the role of morality in the political environment. More specifically, there is significant support for the moral foundations hypothesis that predicts that conservatives tend to draw on virtues associated with binding communities more than liberals (Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, 2009; Graham et al., 2011; Koleva, Graham, Iyer, Ditto, & Haidt, 2012)’ (Davis, Dooley, Hook, Choe, & McElroy, 2017, p. 128).

And although it is usually categorised as psychology, Moral Foundations Theory is also fruitfully considered as philosophy (and perhaps as anthropology). For all its flaws, it’s hard not to love it.

What the Theory Claims

Moral Foundations Theory is the conjunction of four claims.[1]

The first is a form of nativism:

‘the human mind is organized in advance of experience so that it is prepared to learn values, norms, and behaviors related to a diverse set of recurrent adaptive social problems’ (Graham et al., 2013, p. 63).

Second, moral psychology is affected by cultural learning (‘The first draft of the moral mind gets edited during development within a culture.’)

Third, the Social Intuitionist Model of Moral Judgement is true. This is a set of hard-to-understand claims in itself (which we already considered briefly in Moral Disengagement: Significance). Two of these are:

‘moral evaluations generally occur rapidly and automatically, products of relatively effortless, associative, heuristic processing that psychologists now refer to as System 1 thinking’ (Graham et al., 2013, p. 66)

and:

‘moral reasoning is done primarily for socially strategic purposes’ (Graham et al., 2013, p. 66)

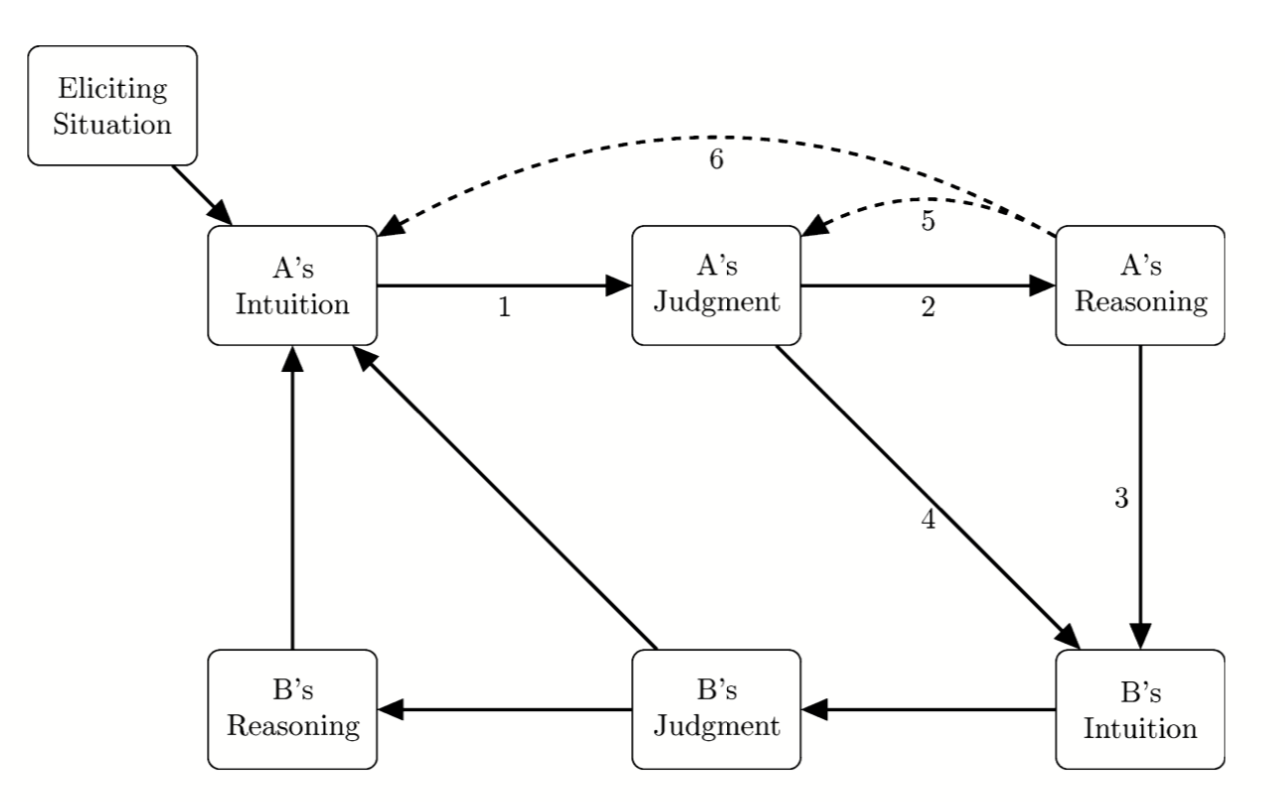

The Social Intuitionist Model is depicted in this figure:

Figure: The Social Intuitionist Model of Moral Judgement. Arrows are interpreted causally. Dotted lines represent connections of low significance. Source: Haidt & Bjorklund (2008, p. figure 4.1)

Figure: The Social Intuitionist Model of Moral Judgement. Arrows are interpreted causally. Dotted lines represent connections of low significance. Source: Haidt & Bjorklund (2008, p. figure 4.1)

Fourth, moral pluralism is true. (‘There are many psychological foundations of morality’ (Graham et al., 2019, p. 212).) This was the topic of Moral Pluralism: Beyond Harm. Haidt & Joseph (2004).

Haidt & Graham (2007) claim that there are five evolutionarily ancient, psychologically basic abilities linked to:

- harm/care

- fairness (including reciprocity)

- in-group loyalty

- respect for authorty

- purity, sanctity

It is not important to the theory that these be the only foundations, nor that these be exactly the foundations. Some researchers have proposed that additional foundations are needed.[2] In more recent work involving the original authors (Haidt and Graham), six foundations are distinguished: what was previously Fairness is split into two things: Equality (which concerns equal treatment) and Proportionality (which concerns being rewarded in proportion to one’s contribution).[3]

What makes something a moral foundation? Where I simplfied above by saying ‘evolutionarily ancient, psychologically basic’, the standard is more demanding:

‘(a) being common in third-party normative judgments, (b) automatic affective evaluations,[4] (c) cultural ubiquity though not necessarily universality, (d) evidence of innate preparedness, and (e) a robust preexisting evolutionary model.’ (Atari et al., 2023, p. 1158)

Glossary

References

Endnotes

Graham et al. (2019) is probably the most accessible introduction, and this is the main source I follow in the lectures. Although a book chapter, it is available online. Haidt (2007) is useful if you are short of time. The theory first appears in Haidt & Graham (2007). ↩︎

To illustrate, Moral Foundations Theory has had some difficulties with Qeirat, a type of honour focussed on family, friends and community that is closely related to mate retention and ‘protecting a loved or sacred thing or person against intrusion’ (Atari, Graham, & Dehghani, 2020, p. 369). And with Libertarians ...

‘Libertarians have a unique moral-psychological profile, endorsing the principle of liberty as an end and devaluing many of the moral concerns typically endorsed by liberals or conservatives’ (Iyer et al., 2012, p. 21).

Since ‘MFT’s five moral foundations appeared to be inadequate in capturing libertarians’ moral concerns, [we decided to] to consider Liberty/oppression as a candidate for addition to our list of foundations’ (Graham et al., 2013, p. 87). ↩︎

The new foundations are called Care, Equality, Proportionality, Loyalty, Authority and Purity (Atari et al., 2023, p. table 2, 1161). These researchers cite Meindl, Iyer, & Graham (2019) as justifying the distinction between equality and proportionality. ↩︎

Given the mixed evidence on the role of feelings and emotions in moral intuitions, (see Moral Intuitions and Emotions: Evaluating the Evidence), one might question whether anything meets all five of these criteria for being a foundation. It may be possible to substitue revised criteria which involve fewer bold empirical committments but still capture the core idea that some aspects of ethical judgements are more foundational than others. ↩︎