Question Session 03

There are no question sessions this year, but some of the notes

from previous years are still relevant. These are included here.

Notes

What Are Moral Intuitions?

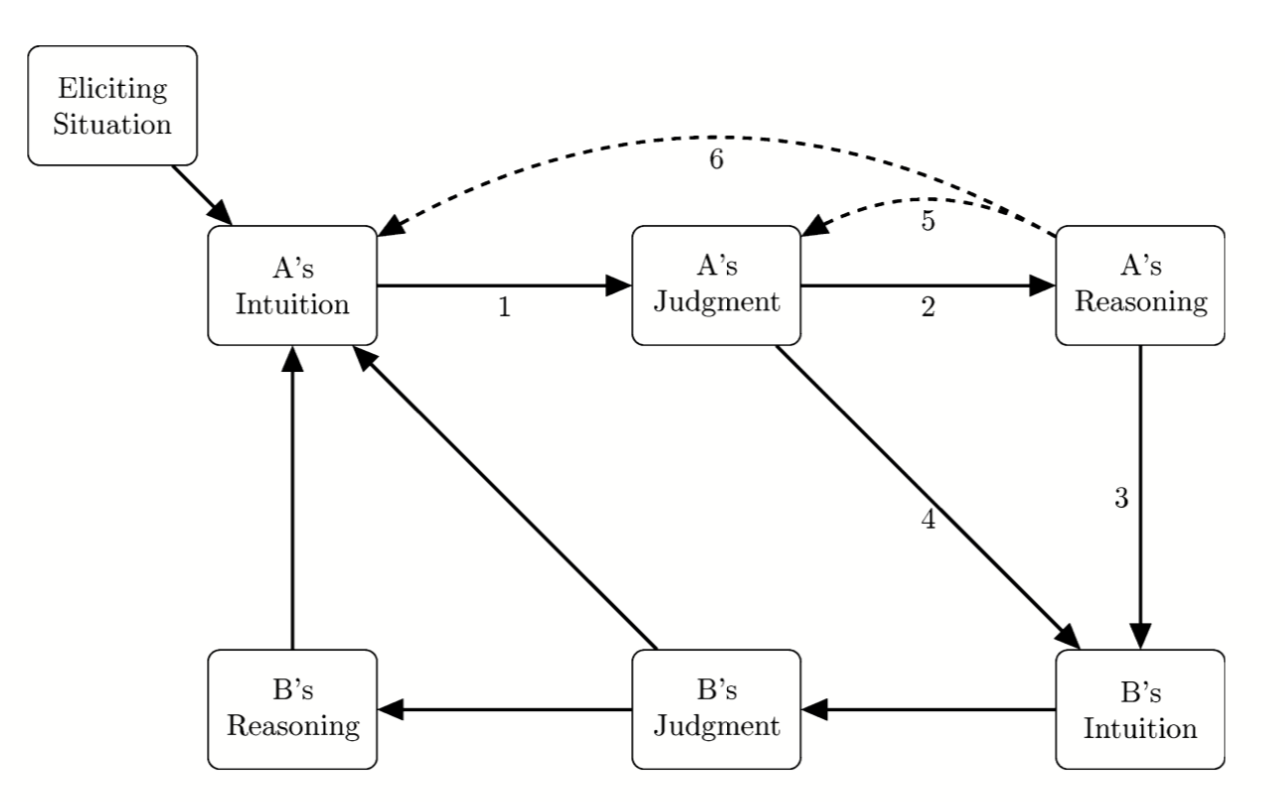

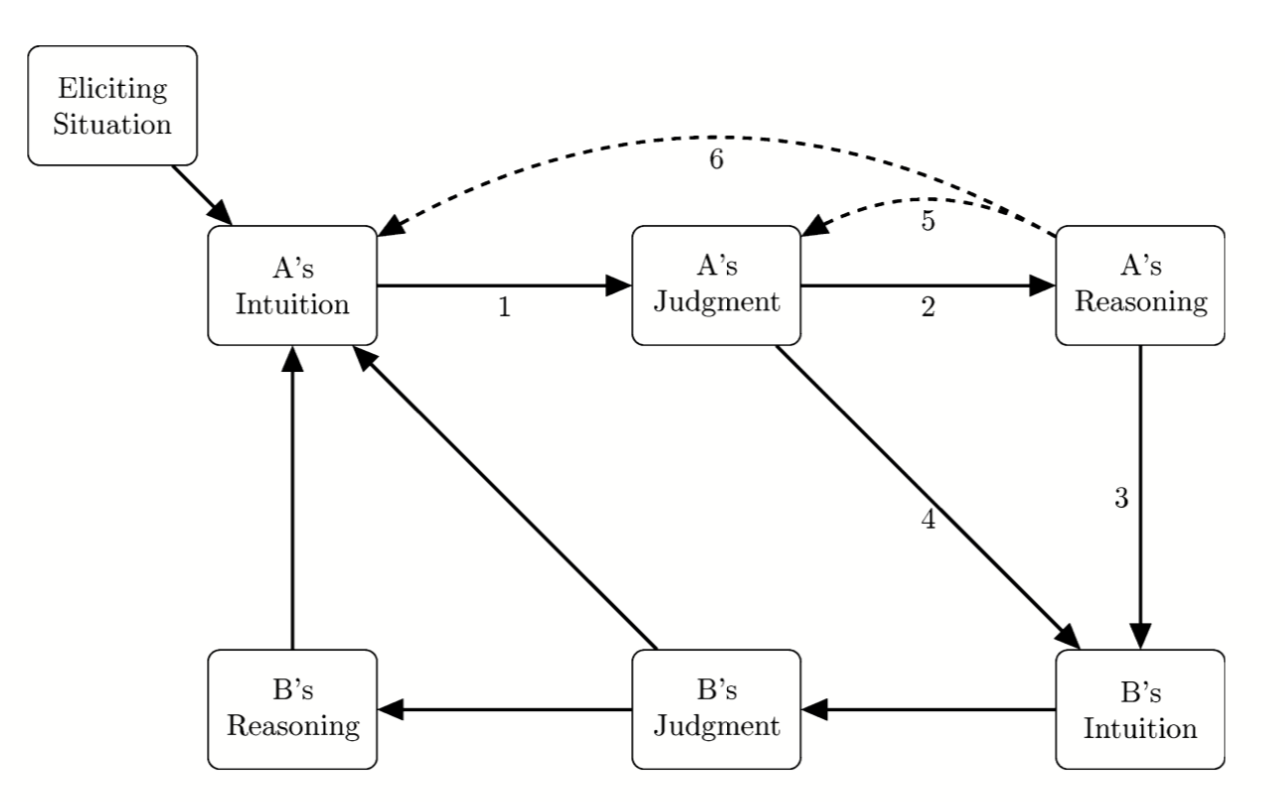

Svenja made an objection about moral intuitions and the Social Intuitionist Model of Moral Judgement

presented in Haidt & Bjorklund (2008) (see figure below; this was discussed in Moral Disengagement: Significance).

Figure: The Social Intuitionist Model of Moral Judgement Source: Haidt & Bjorklund (2008, p. figure 4.1)

Figure: The Social Intuitionist Model of Moral Judgement Source: Haidt & Bjorklund (2008, p. figure 4.1)

On this model, moral intuitions cannot be unreflective judgements (because on that definition, intuitions are judgements; it would make little sense to depict them as causes of judgements).

Nor, on this model can moral intuitions be ‘strong, stable, immediate moral beliefs’ (Sinnott-Armstrong, Young, & Cushman, 2010, p. 256). For then it would make sense to regard them as causes of judgements, but

probably only through processes of reasoning. Further, Haidt & Bjorklund (2008, p. 181)

assert that

‘moral judgment is a product of

quick

and automatic intuitions.’

Since a belief cannot be quick (nor slow), Haidt and Bjorklund cannot be thinking of

moral intuitions as Sinnott-Armstrong et al. do.

Conclusion: Different researchers use the term ‘moral intuition’ for different things. It is

not always easy to work out which things they are using it for.

Glossary

moral disengagement :

Moral disengagement occurs when self-sanctions are disengaged from

conduct. To illustrate, an executioner may avoid self-sanctioning for killing

by reframing the role they play as ‘babysitting’ (Bandura, 2002, p. 103).

Bandura (2002, p. 111) identifies several

mechanisms of moral disengagement: ‘The disengagement may centre on

redefining harmful conduct as honourable by moral justification, exonerating

social comparison and sanitising language. It may focus on agency of action

so that perpetrators can minimise their role in causing harm by diffusion

and displacement of responsibility. It may involve minimising or distorting

the harm that follows from detrimental actions; and the disengagement may

include dehumanising and blaming the victims of the maltreatment.’

moral dumbfounding :

‘the stubborn and puzzled maintenance of an [ethical] judgment without supporting reasons’ (Haidt, Bjorklund, & Murphy, 2000, p. 1). As McHugh, McGann, Igou, & Kinsella (2017) note, subsequent researchers have given different definitions of moral dumbfounding so that ‘there is [currently] no single, agreed definition of moral dumbfounding.’ I adopt the original authors’ definition, as should you unless there are good reasons to depart from it.

moral intuition :

According to this lecturer, a person’s intuitions are the claims they take to be true

independently of whether those claims are justified inferentially. And a person’s moral intuitions are

simply those of their intuitions that concern ethical matters.

According to Sinnott-Armstrong et al. (2010, p. 256), moral intuitions are ‘strong, stable, immediate moral beliefs.’

Social Intuitionist Model of Moral Judgement :

A model on which intuitive processes are directly responsible for moral judgements (Haidt & Bjorklund, 2008).

One’s own reasoning does not typically affect one’s own moral judgements,

but (outside philosophy, perhaps) is typically used only to provide post-hoc justification

after moral judgements are made.

Reasoning does affect others’ moral intuitions, and so provides a mechanism for cultural learning.

References

Bandura, A. (2002). Selective Moral Disengagement in the Exercise of Moral Agency.

Journal of Moral Education,

31(2), 101–119.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0305724022014322Decety, J., & Cacioppo, S. (2012). The speed of morality: A high-density electrical neuroimaging study.

Journal of Neurophysiology,

108(11), 3068–3072.

https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00473.2012Haidt, J., & Bjorklund, F. (2008). Social intuitionists answer six questions about moral psychology. In W. Sinnott-Armstrong (Ed.),

Moral psychology, Vol 2: The cognitive science of morality: Intuition and diversity (pp. 181–217). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT press.

Haidt, J., Bjorklund, F., & Murphy, S. (2000).

Moral dumbfounding: When intuition finds no reason.

Unpublished manuscript, University of Virginia.

Huebner, B., Dwyer, S., & Hauser, M. (2009). The role of emotion in moral psychology.

Trends in Cognitive Sciences,

13(1), 1–6.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.09.006McHugh, C., McGann, M., Igou, E. R., & Kinsella, E. L. (2017). Searching for Moral Dumbfounding: Identifying Measurable Indicators of Moral Dumbfounding.

Collabra: Psychology,

3(1), 23.

https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.79Paxton, J. M., & Greene, J. D. (2010). Moral Reasoning: Hints and Allegations.

Topics in Cognitive Science,

2(3), 511–527.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2010.01096.xPiazza, J., Landy, J. F., Chakroff, A., Young, L., & Wasserman, E. (2018). What disgust does and does not do for moral cognition. In N. Strohminger & V. Kumar (Eds.),

The moral psychology of disgust (pp. 53–81). Rowman & Littlefield International.

Sinnott-Armstrong, W., Young, L., & Cushman, F. (2010). Moral intuitions. In J. M. Doris, M. P. R. Group, & others (Eds.),

The moral psychology handbook (pp. 246–272). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ugazio, G., Lamm, C., & Singer, T. (2012). The Role of Emotions for Moral Judgments Depends on the Type of Emotion and Moral Scenario.

Emotion,

12(3), 579–590.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024611

Endnotes

Figure: The Social Intuitionist Model of Moral Judgement Source: Haidt & Bjorklund (2008, p. figure 4.1)

Figure: The Social Intuitionist Model of Moral Judgement Source: Haidt & Bjorklund (2008, p. figure 4.1)