Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

(If the slides don’t work, you can still use any direct links to recordings.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Moral Intuitions and Heuristics: First Pass

Sinnott-Armstrong et al (2010), ‘Moral Intuitions’ in Doris et al (ed)

What are moral intutions?

Unreflective ethical / linguistic / mathematical judgements

[1] He is a waffling fatberg of lies.

[2]* A waffling fatberg lies of he is.

Two projects -- everyday life vs philosophy

What do adult humans compute that enables their unreflective judgements to track moral attributes (such as wrongness)?

1. Moral attributes are inaccessible.

‘We adopt the term accessibility to refer to the ease (or effort) with which particular mental contents come to mind’

Kahneman and Frederick, 2005 p. 271

2. Unreflective ethical judgements are (often enough) fast.

3. Computing inaccessible attributes is slow.

Therefore:

4. Making unreflective ethical judgements does not involve computing moral attributes.

What do adult humans compute that enables their unreflective judgements to track toxicity?

1. Toxicity is an inaccessible attribute.

2. Unreflective toxicity judgements are (often enough) fast.

3. Computing inaccessible attributes is slow.

Therefore:

4. Making unreflective toxicity judgements does not involve computing toxicity.

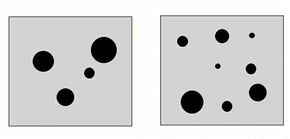

Inaccessible attribute:

- toxicity

Accessible attribute:

- how smelling it makes me feel

Heuristic: if smelling it makes you feel disgust, judge that it is toxic.

What do adult humans compute that enables their unreflective judgements to track toxicity?

1. Toxicity is an inaccessible attribute.

2. Unreflective toxicity judgements are (often enough) fast.

3. Computing inaccessible attributes is slow.

Therefore:

4. Making unreflective toxicity judgements does not involve computing toxicity.

How is this relevant to the question about moral intuition?

What do adult humans compute that enables their unreflective judgements to track moral attributes (such as wrongness)?

1. Moral attributes are inaccessible.

2. Unreflective ethical judgements are (often enough) fast.

3. Computing inaccessible attributes is slow.

Therefore:

4. Making unreflective ethical judgements does not involve computing moral attributes.

Inaccessible attribute:

- rightness or wrongness (e.g.)

Accessible attribute:

Which accessible properties could be used in moral heuristics?

- how thinking about it makes me feel

the ‘affect heuristic’:

‘if thinking about an act [...] makes you feel bad [...], then judge that it is morally wrong’.

Sinnott-Armstrong et al, 2010

What do adult humans compute that enables their unreflective judgements to track moral attributes (such as wrongness)?

1. Moral attributes are inaccessible.

2. Unreflective ethical judgements are (often enough) fast.

3. Computing inaccessible attributes is slow.

Therefore:

4. Making unreflective ethical judgements does not involve computing moral attributes.

Sinnott-Armstrong et al (2010)’s claims about moral intuitions

Moral attributes are inaccessible.

‘Inaccessibility creates the need for a heuristic attribute’ (p. 257).

I.e. moral intuitions do not involve computing moral attributes.

Instead they involve using heuristics, i.e. computing accessible attributes which are correlated with moral attributes ...

... and, in particular, whether thinking about something makes you feel bad ('the affect heuristic').

Implications

Epistemic: ‘if moral intuitions result from heuristics, [... philosophers] must stop claiming direct insight into moral properties’

Should we trust moral intuitions? ‘Just as non-moral heuristics lack reliability in unusual situations, so do moral intuitions’

-- relevance: defending consequentialism