Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

(If the slides don’t work, you can still use any direct links to recordings.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Moral Foundations Theory: An Approach to Cultural Variations

aims

‘a systematic theory of morality, explaining its origins, development, and cultural variations’

It’s not all about harm.

e.g. food taboos; obedience

There may be cultural variations on what is ethical and what isn’t.

So we can’t assume in advance that we know what is ethical and what isn’t.

But if we don’t know what is ethical and what isn’t, how can we study cultural variations in it?

[nativism] ‘There is a first draft of the moral mind’

[cultural learning] ‘The first draft of the moral mind gets edited during development within a culture’

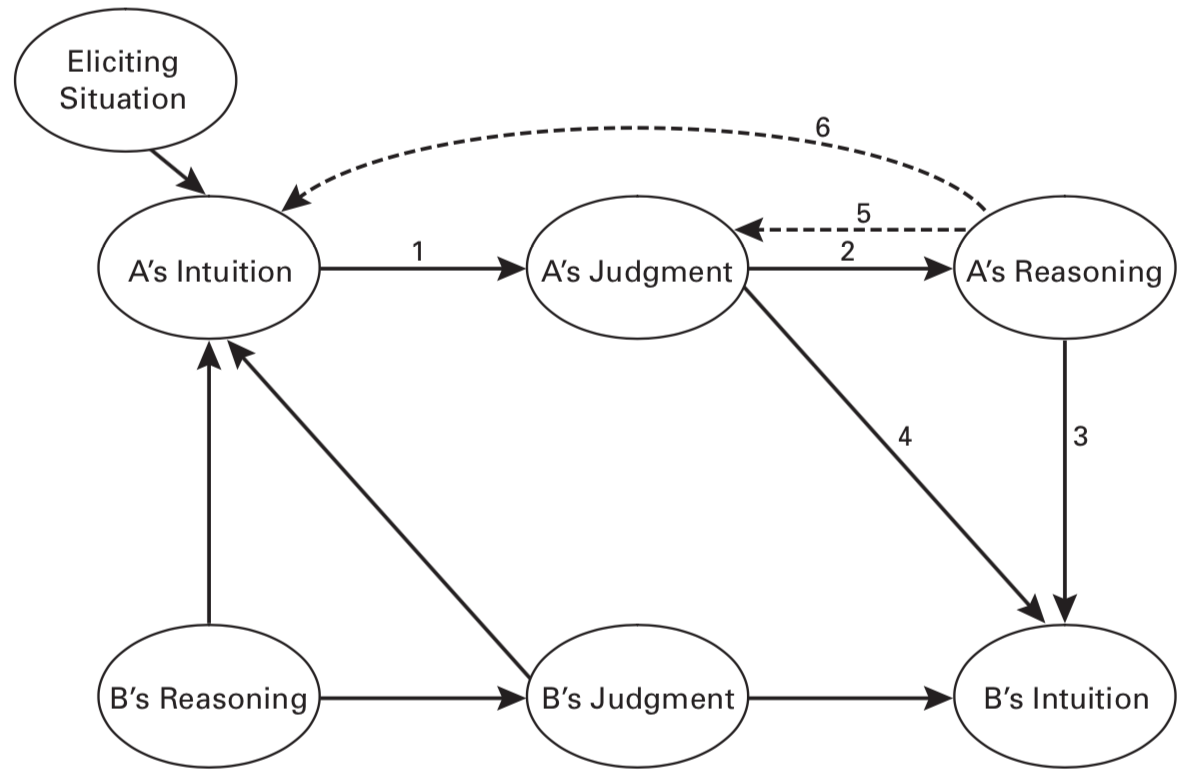

[intuitionism] ‘Intuitions come first’ --- the Social Intuitionist Model is true

Haidt & Bjorklund, 2008 figure 4.1

[nativism] ‘There is a first draft of the moral mind’

[cultural learning] ‘The first draft of the moral mind gets edited during development within a culture’

[intuitionism] ‘Intuitions come first’ --- the Social Intuitionist Model is true

[pluralism] ‘There are many psychological foundations of morality’

Graham et al, 2019

Individual:

harm/care

fairness (including reciprocity)

Binding:

in-group loyalty

respect for authorty

[purity, sanctity]

[nativism] ‘There is a first draft of the moral mind’

[cultural learning] ‘The first draft of the moral mind gets edited during development within a culture’

[intuitionism] ‘Intuitions come first’ --- the Social Intuitionist Model is true

[pluralism] ‘There are many psychological foundations of morality’

Graham et al, 2019

2

‘Moral-foundations researchers have investigated the similarities and differences in morality among individuals across cultures (Haidt & Josephs, 2004). These researchers have found evidence for five fundamental domains of human morality’

Feinberg & Willer, 2013 p. 1

Moral Foundations Questionnaire

Example: Harm

[relevance] How morally relevant is each of the following?

Whether or not someone suffered emotionally

Whether or not someone cared for someone weak or vulnerable

Whether or not someone was cruel

[judgement] To what extent do you agree with each of the following?

Compassion for those who are suffering is the most crucial virtue.

One of the worst things a person could do is hurt a defenseless animal.

It can never be right to kill a human being

Basic requirements

- internal validity (roughly, do answers to the three questions appear to reflect a single underlying tendency)

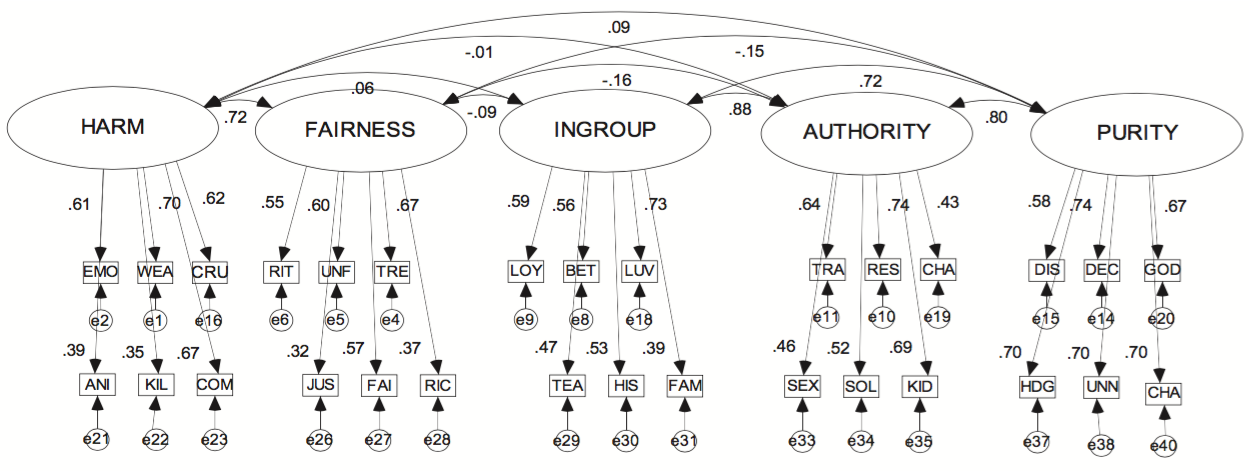

Graham et al, 2011 figure 3 (part)

Confirmatory factor analysis

observed variables : answers to individual MFQ questions

latent factors : the five moral primitives

clear nontechnical intro to confirmatory factor analysis (& more): Gregorich, 20006

Graham et al, 2011 figure 3 (part)

‘The five-factor model fit the data better (weighing both fit and parsimony) than competing models, and this five-factor representation provided a good fit for participants in 11 different world areas.’

Graham et al, 2011 p. 380

‘[...] empirical support for the MFQ for the first time in a predominantly Muslim country. [...] the 5-factor model, although somewhat below the standard criteria of fitness, provided the best fit among the alternatives.

Yilmaz et al, 2016 p. 153

Basic requirements

- internal validity (roughly, do answers to the three questions appear to reflect a single underlying tendency)

- Test–retest reliability (are you as an individual likely to give the same answers at widely-spaced intervals?)

- external validity (relation to other scales)

- measurement invariance [we’ll come to this later]

There may be cultural variations on what is ethical and what isn’t.

So we can’t assume in advance that we know what is ethical and what isn’t.

But if we don’t know what is ethical and what isn’t, how can we study cultural variations in it?

Does MFT answer this question?

fieldwork -> hypothetical model -> CFA -> revise model -> ...

an application: pathogens

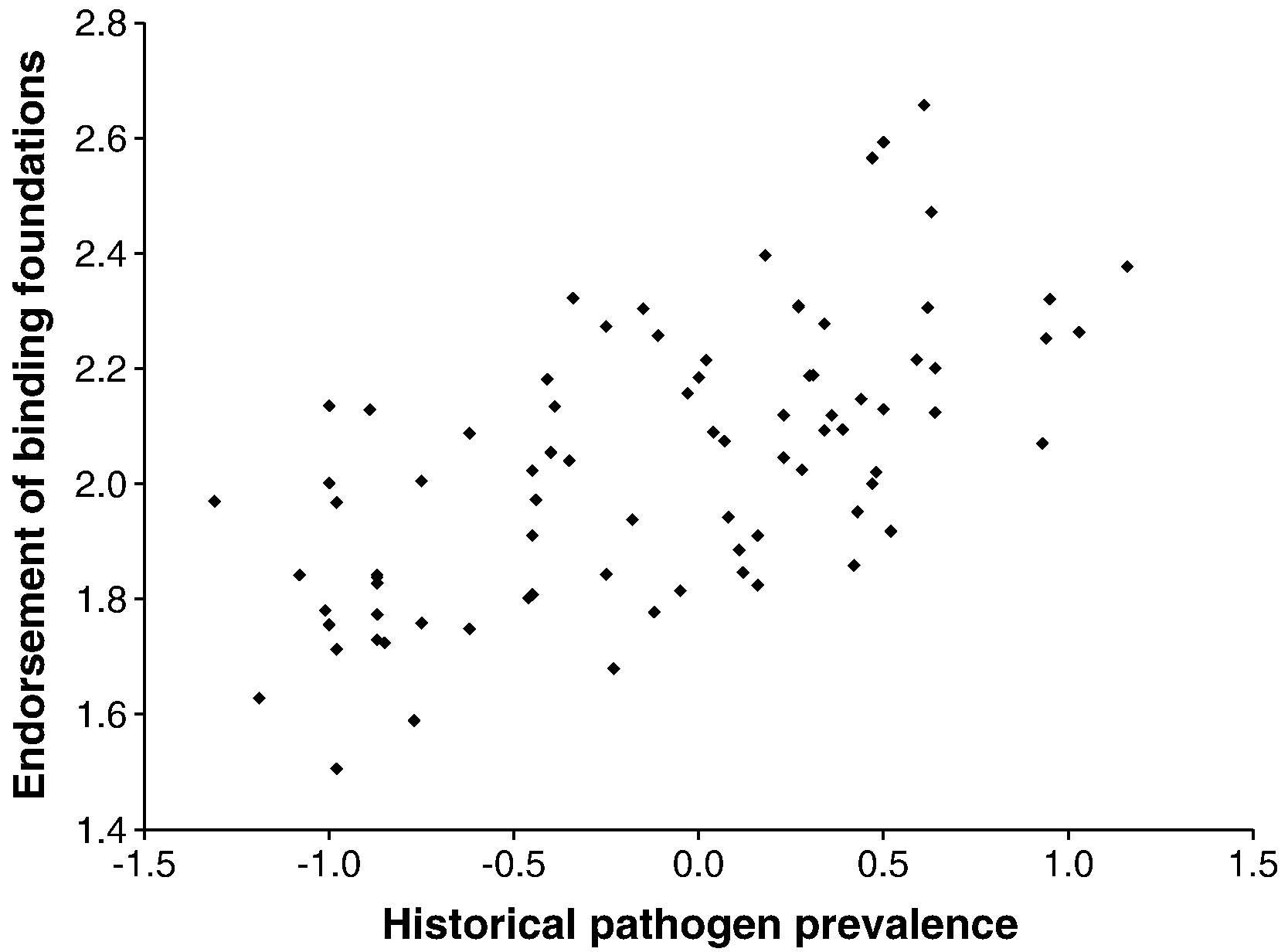

van Leeuwen et al, 2012 figure 1

‘historical pathogen prevalence---even when controlling for individual-level variation in political orientation, gender, education, and age---significantly predicted endorsement of Ingroup/loyalty [stats removed], Authority/respect, and Purity/sanctity; it did not predict endorsement of Harm/care or Fairness/reciprocity’

van Leeuwen et al, 2012

Argument for pluralism

2

‘Moral-foundations researchers have investigated the similarities and differences in morality among individuals across cultures (Haidt & Josephs, 2004). These researchers have found evidence for five fundamental domains of human morality’

Feinberg & Willer, 2013 p. 1