Click here and press the right key for the next slide (or swipe left)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Moral Psychology vs Consequentialism?

[email protected]

linguistic / mathematical / aesthetic /

ethical

abilities

- act

- judge

- be open to moral suasion

- feel

Moral psychology is the study of psychological aspects of ethical abilities.

What ethical abilities do humans have? What states and processes underpin them?

What, if anything, do discoveries about ethical abilities imply about ethics?

Course Structure

Part 1: psychological underpinnings of ethical abilities

Part 2: implications for ethics?

‘Science can advance ethics by revealing the hidden inner workings of our moral judgments, especially the ones we make intuitively. Once those inner workings are revealed we may have less confidence in some of [...] the ethical theories that are explicitly or implicitly based on them’

Greene, 2014 pp. 695--6

Course Structure

Part 1: psychological underpinnings of ethical abilities

Part 2: implications for ethics?

Trolley

A runaway trolley is about to run over and kill five people. You can hit a switch that will divert the trolley onto a different set of tracks where it will kill only one.

Is it okay to hit the switch?

Trolley

A runaway trolley is about to run over and kill five people. You can hit a switch that will divert the trolley onto a different set of tracks where it will kill only one.

Is it okay to hit the switch?

Transplant

Five people are going to die but you can save them all by cutting up one healthy person and distributing her organs.

Is it ok to cut her up?

puzzle 1

Why do people tend to respond differently in Trolley and Transplant?

Moral Dumbfounding

Hypothesis: Not all unreflective moral judgements depend on reasoning.

What is moral dumbfounding?

Haidt et al (2000; unpublished!)’s tasks

Control: ‘Heinz dilemma (should Heinz steal a drug to save his dying wife?)’

morally provocative but ‘harmless’: Incest; Cannibal

nonmorally provocative but ‘harmless’: Roach; Soul

Method: ask whether wrong; counter argue; questionnaire

Haidt et al (2000; unpublished!)’s tasks

Control: ‘Heinz dilemma (should Heinz steal a drug to save his dying wife?)’

morally provocative but ‘harmless’: Incest; Cannibal

nonmorally provocative but ‘harmless’: Roach; Soul

Method: ask whether wrong; counter argue; questionnaire

Results

NB: unpublished data

‘it often happened that participants made “unsupported declarations”, e.g., “It’s just wrong to do that!” or “That’s terrible!”

They made the fewest such declarations in Heinz, and they made significantly more such declarations in the Incest story.’

Results ctd

NB: unpublished data

Informal observation: ‘participants often directly stated that they were dumbfounded, i.e., they made a statement to the effect that they thought an action was wrong but they could not find the words to explain themselves’ (p. 9)

‘Participants made the fewest such statements in Heinz (only 2 such statements, from 2 participants), while they made significantly more such statements in the Incest (38 statements from 23 different participants), Cannibalism (24 from 11), and Soul stories (22 from 13).’

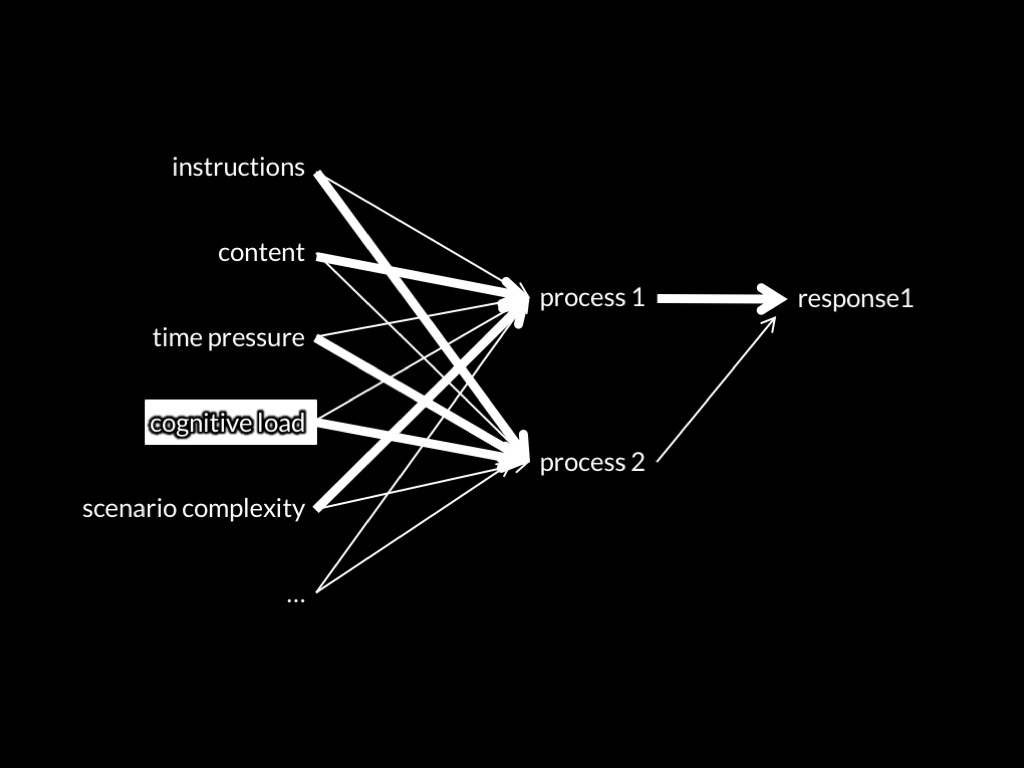

Study 2 (not reported!):

Cognitive load increased the level of moral dumbfounding without changing subjects’ judgments.

replication / extension / review?

‘a definitionally pristine bout of MD is likely to be a extraordinarily rare find, one featuring a person who doggedly and decisively condemns the very same act that she has no prior normative reasons to dislike’

Royzman et al, 2015 p. 311

‘3 of [...] 14 individuals [without supporting reasons] disapproved of the siblings having sex and only 1 of 3 (1.9%) maintained his disapproval in the “stubborn and puzzled” manner.’

Royzman et al, 2015 p. 309

Warning: Note the absent comparison with the Heinz dilemma.

summary: moral dumbfounding

we know the definition;

some evidence --- weak, but probably occurs.

why is this relevant?

Hypothesis: Not all unreflective moral judgements depend on reasoning.

Remember Heinz!

post-hoc rationalization

Moral reasoning merely serves to confirm prior intuitions, in nearly all cases (Haidt; Greene)

ante hoc reasoning

In ordinary cases of moral disengagement, moral reasoning provides anticipatory rationalization (Hendriks, 2015)

My view.

Moral dumbfounding shows that some ethical judgements are not consequences of reasoning from known principles

Other phenomena (e.g. moral disengagement) indicate that some ethical judgements are consequences of reasoning from known principles

puzzle 2

Why are ethical judgements sometimes, but not always, a consequence of reasoning from known principles?

Emotion Drives Unreflective Ethical Judgements

Theoretical Claim: Emotion drives unreflective ethical judgements.

Prediction: Manipulating subjects’ emotions will influence their unreflective ethical judgements.

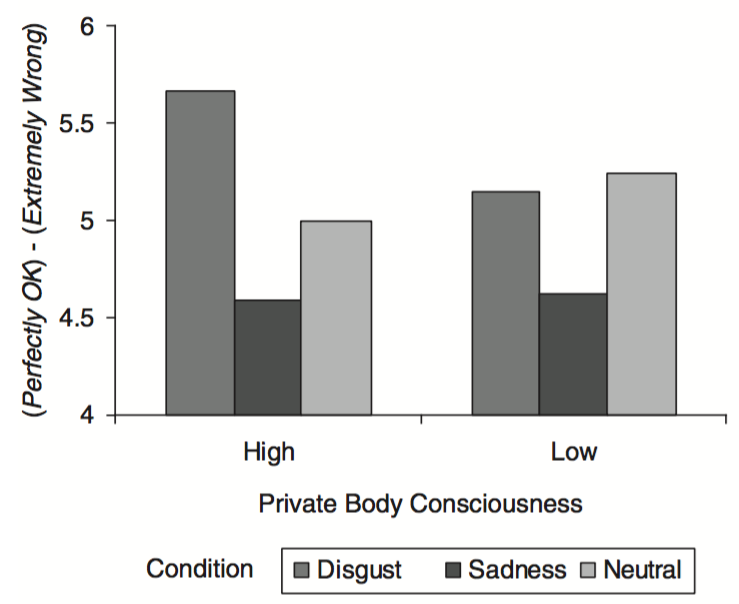

Schnall et al, 2008 Experiment 4

3 groups: induce disgust, sadness or neither using video clips

Judge how wrong an action is in six vignettes

Half the vignettes involve disgusting actions.

Predictions:

Disgust (but not sadness) will influence moral judgements,

irrespective of whether the actions judged are disgusting.

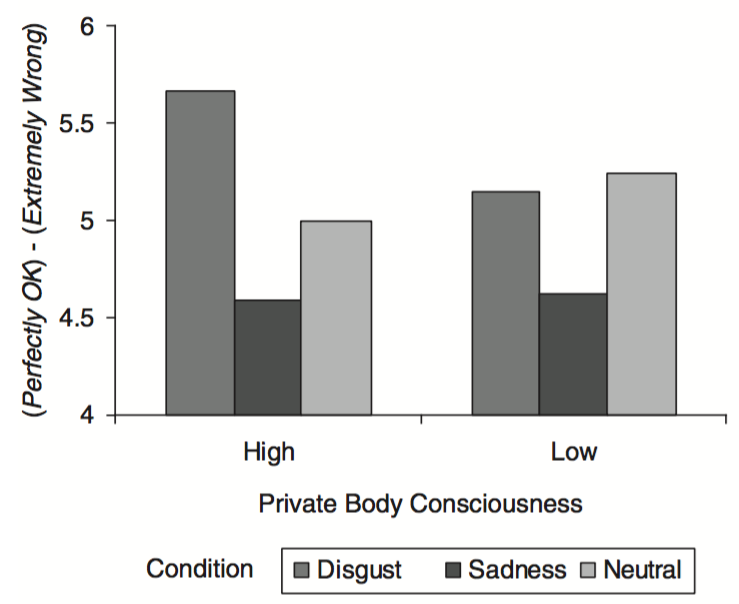

Complication: Private Body Consciousness

Result: ‘disgust influenced moral judgment similarly for both disgust and nondisgust vignettes’.

Schnall et al, 2008 figure 3

Schnall et al, 2008 conclusions:

‘the effect of disgust applies regardless of whether the action to be judged is itself disgusting.

Second, [...] disgust influenced moral, but not additional nonmoral, judgments.

Third, because the effect occurred most strongly for people who were sensitive to their own bodily cues, the results appear to concern feelings of disgust rather than merely the primed concept of disgust.

Fourth, [...] induced sadness did not have similar effects.’

Schnall et al, 2008 pp. 1105--6

Is the prediction confirmed?

Theoretical Claim: Emotion drives unreflective ethical judgements.

Prediction: Manipulating subjects’ emotions will influence their unreflective ethical judgements.

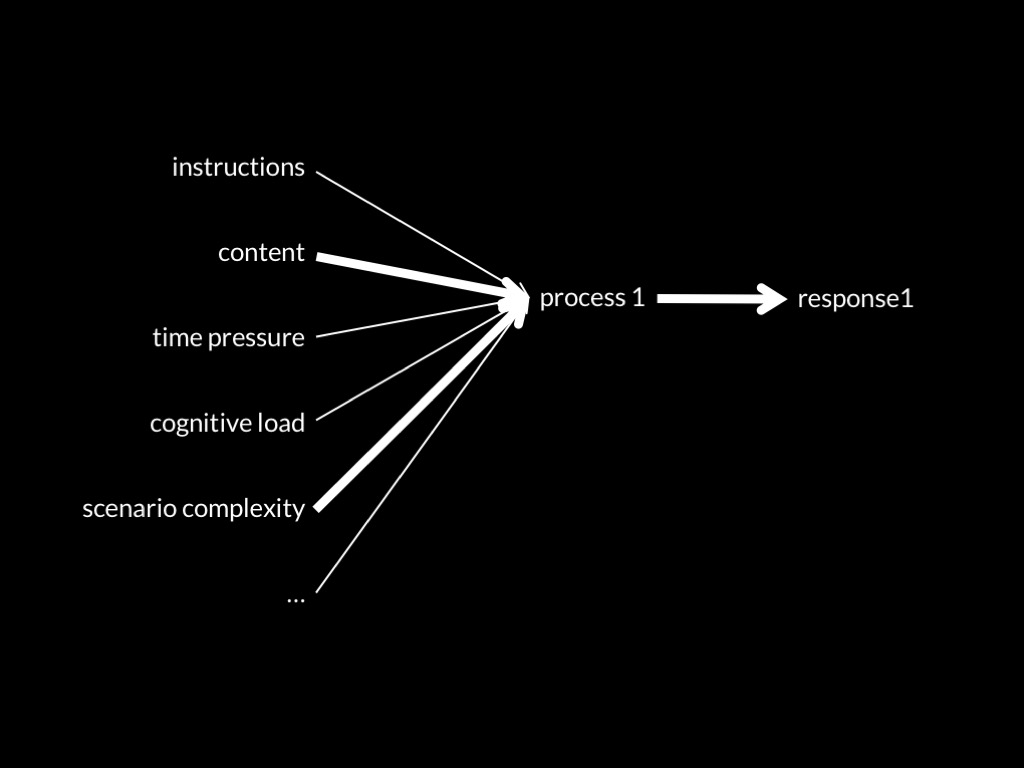

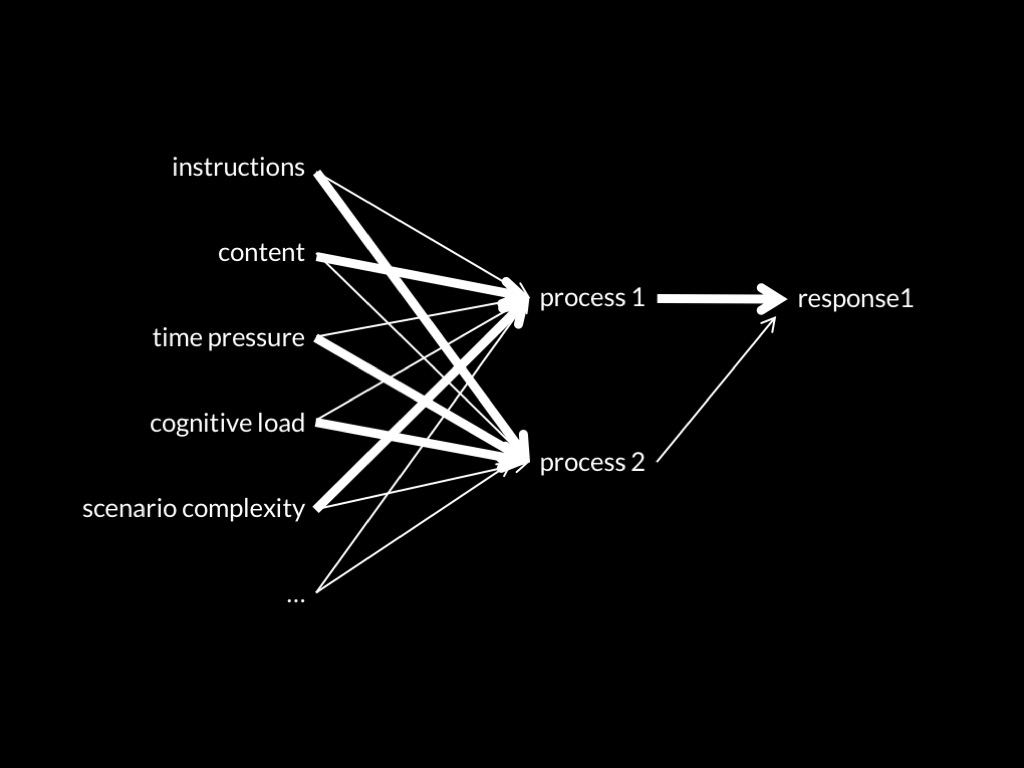

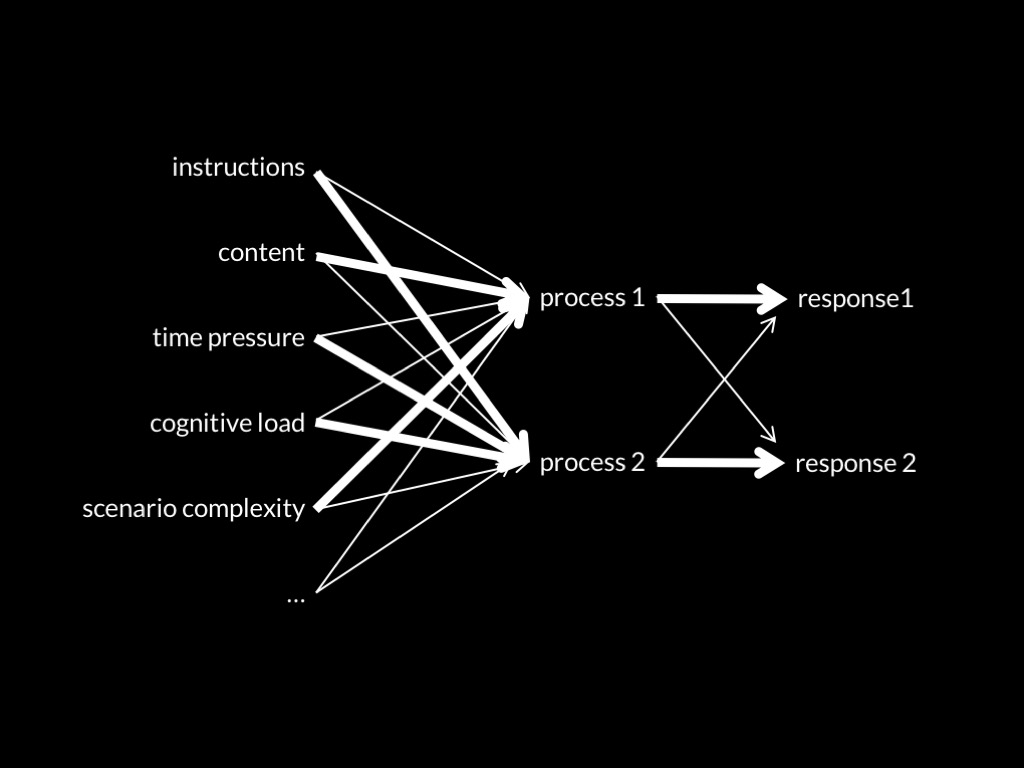

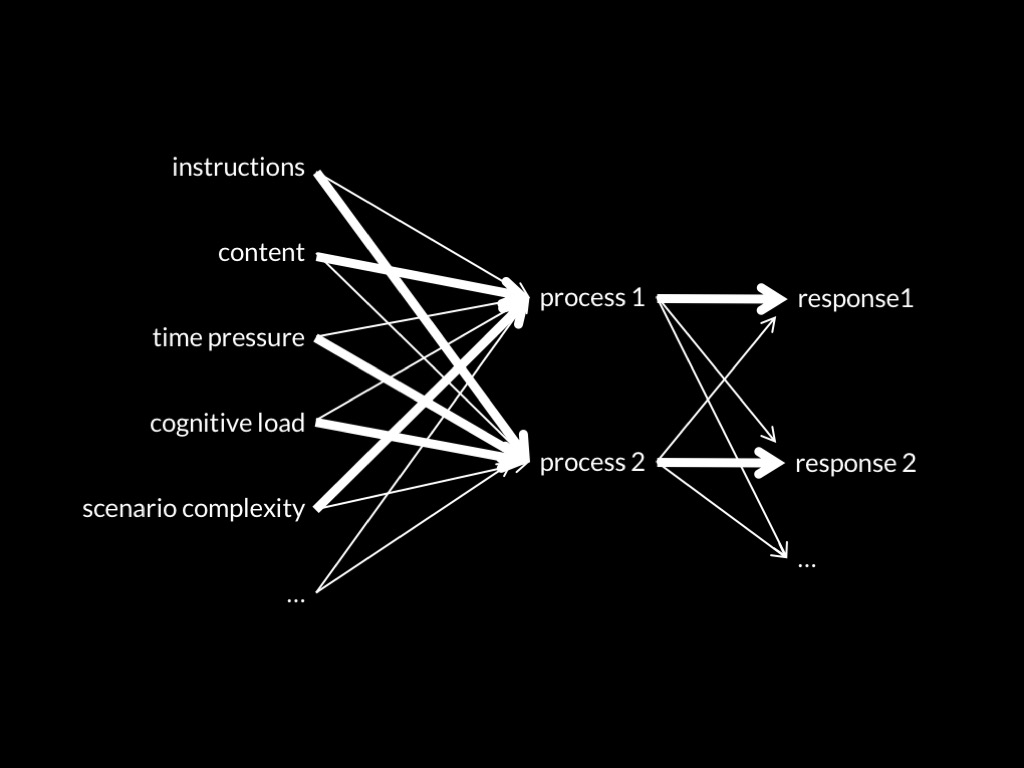

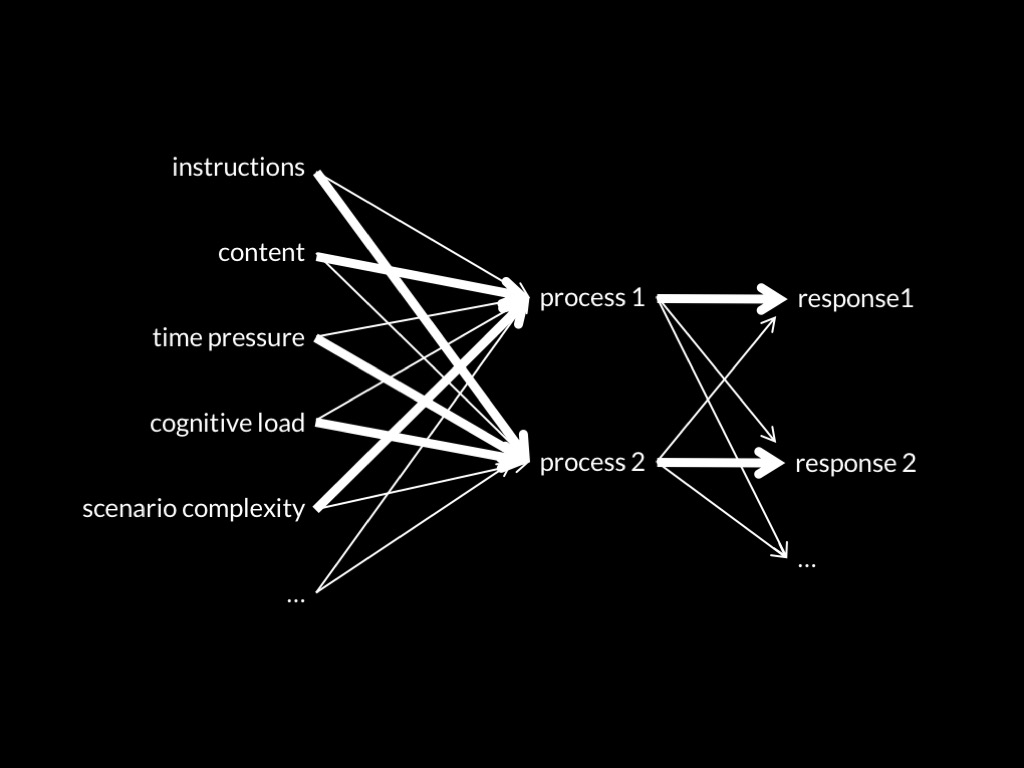

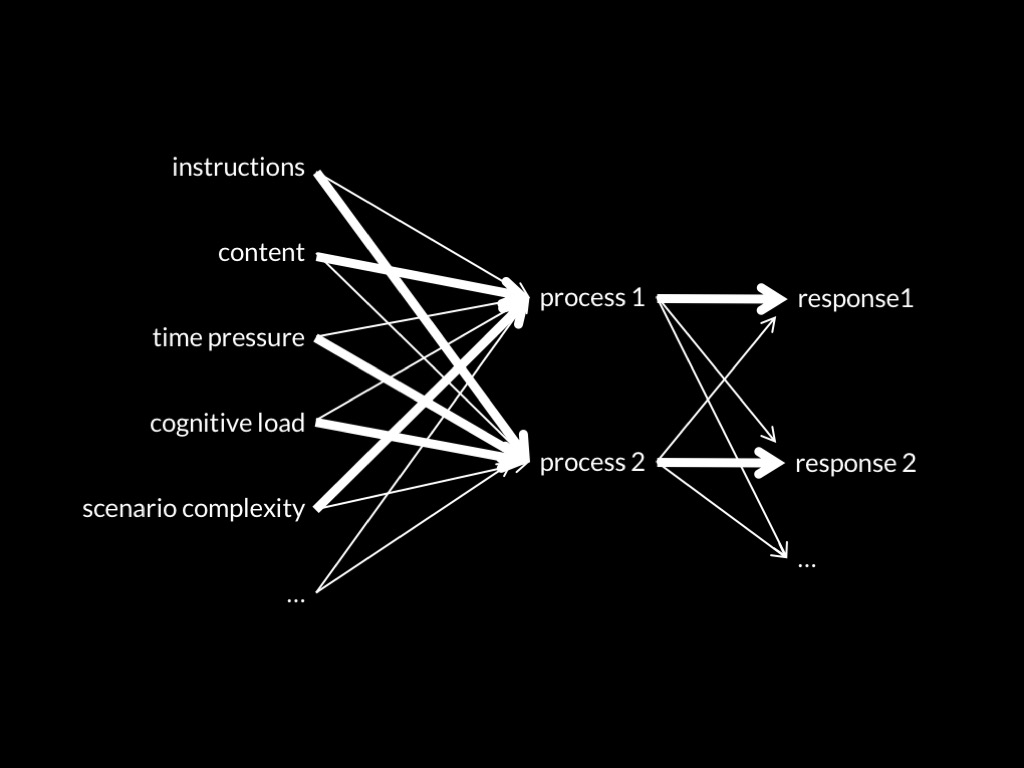

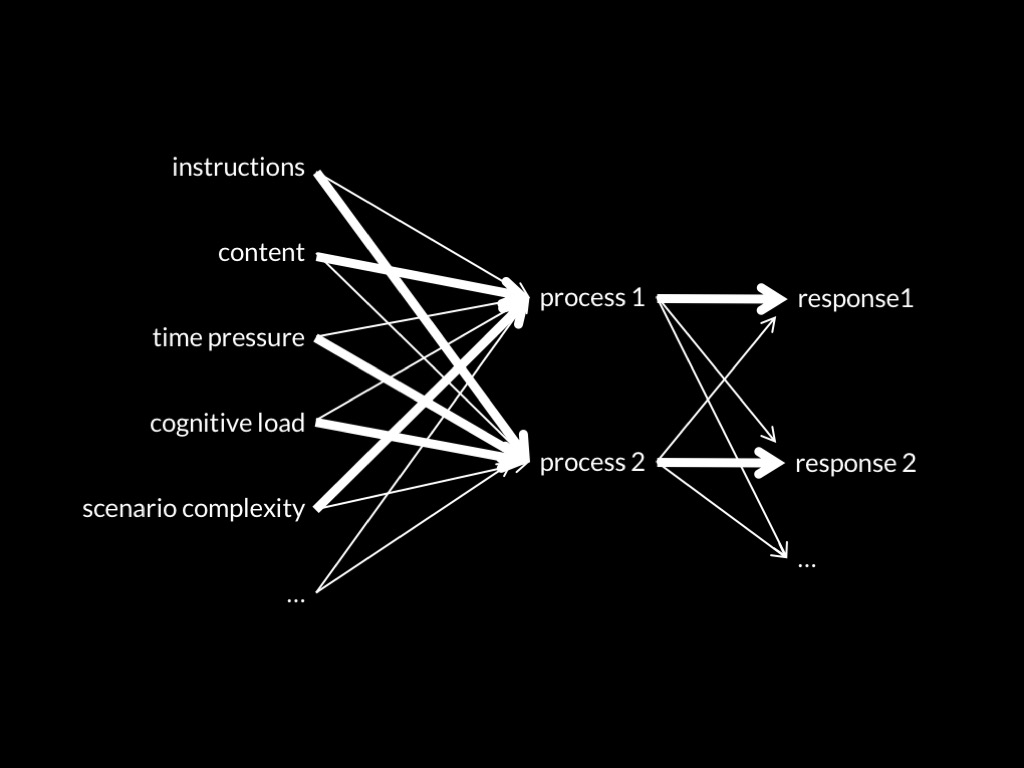

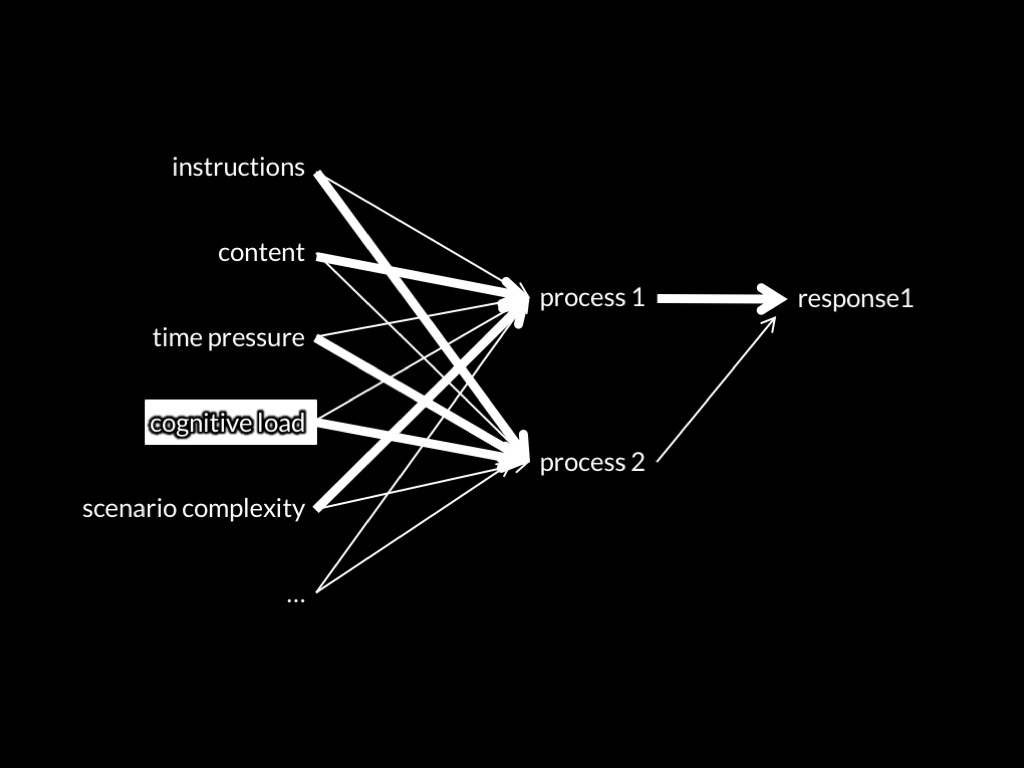

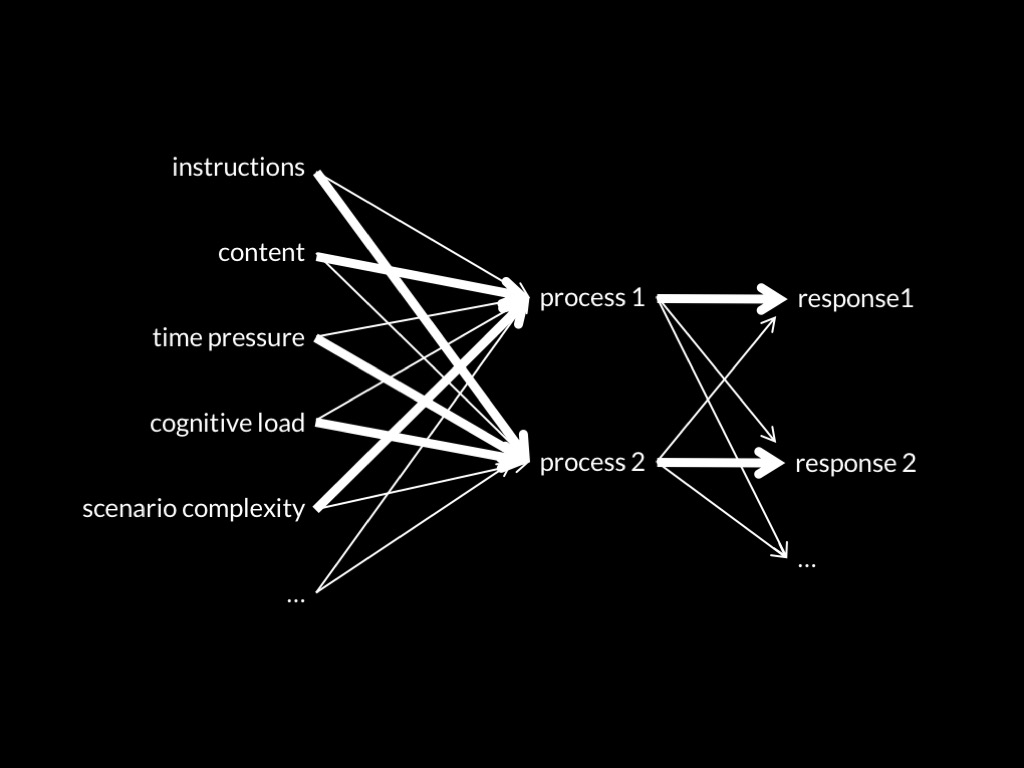

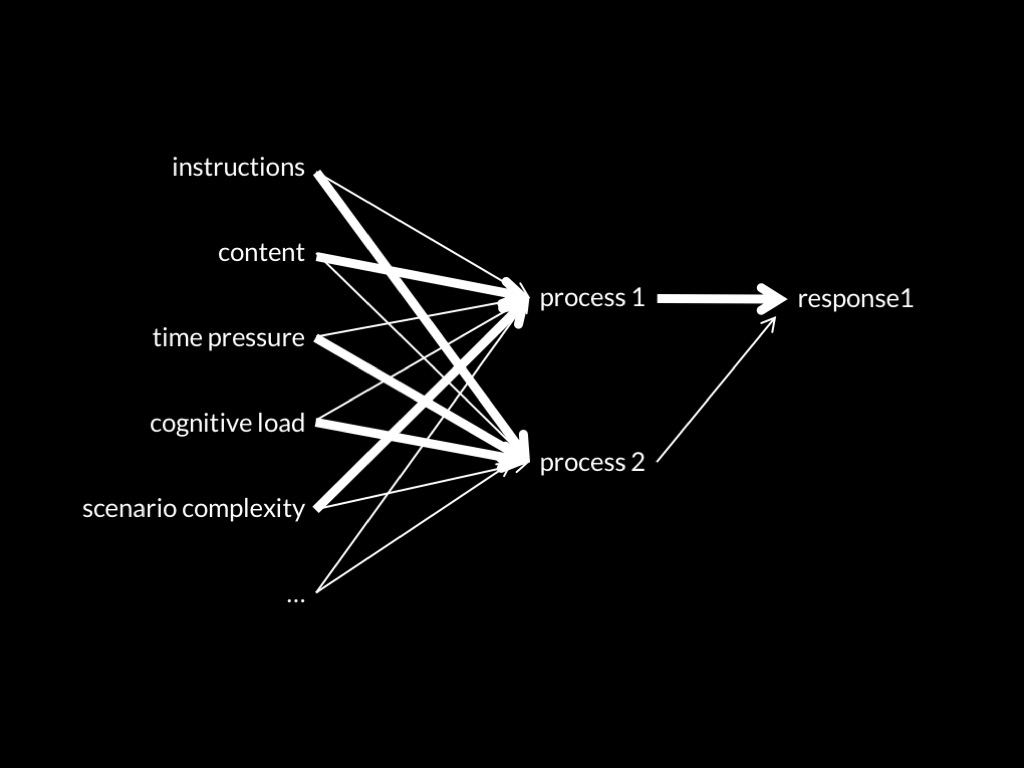

Dual Process Theories

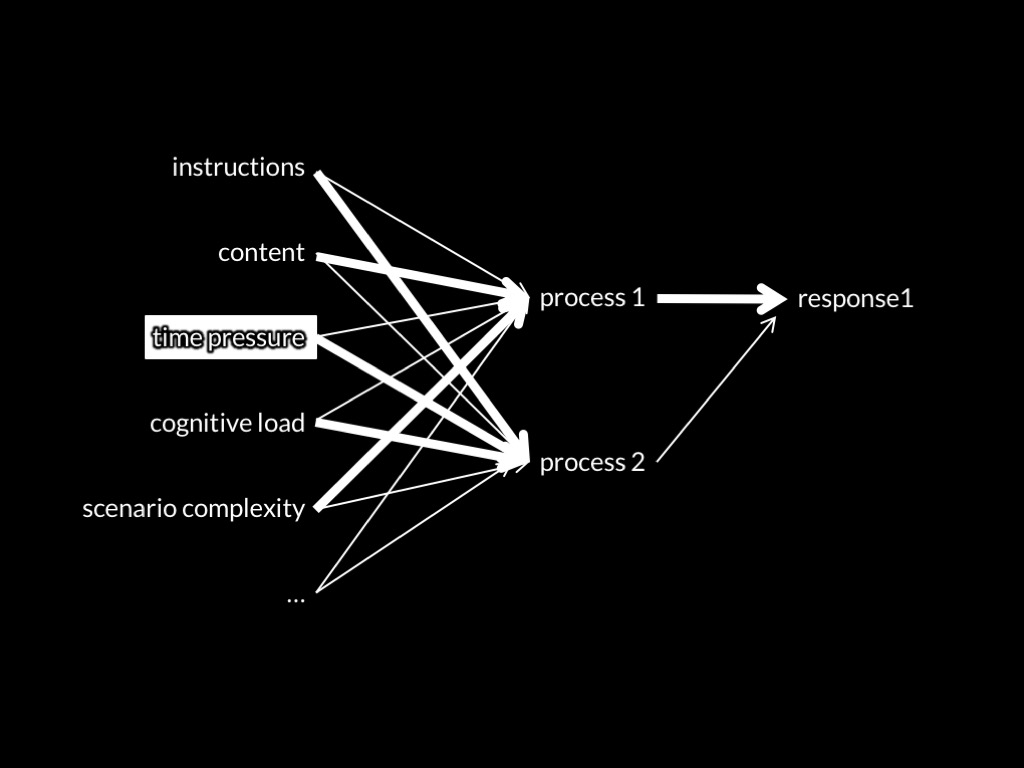

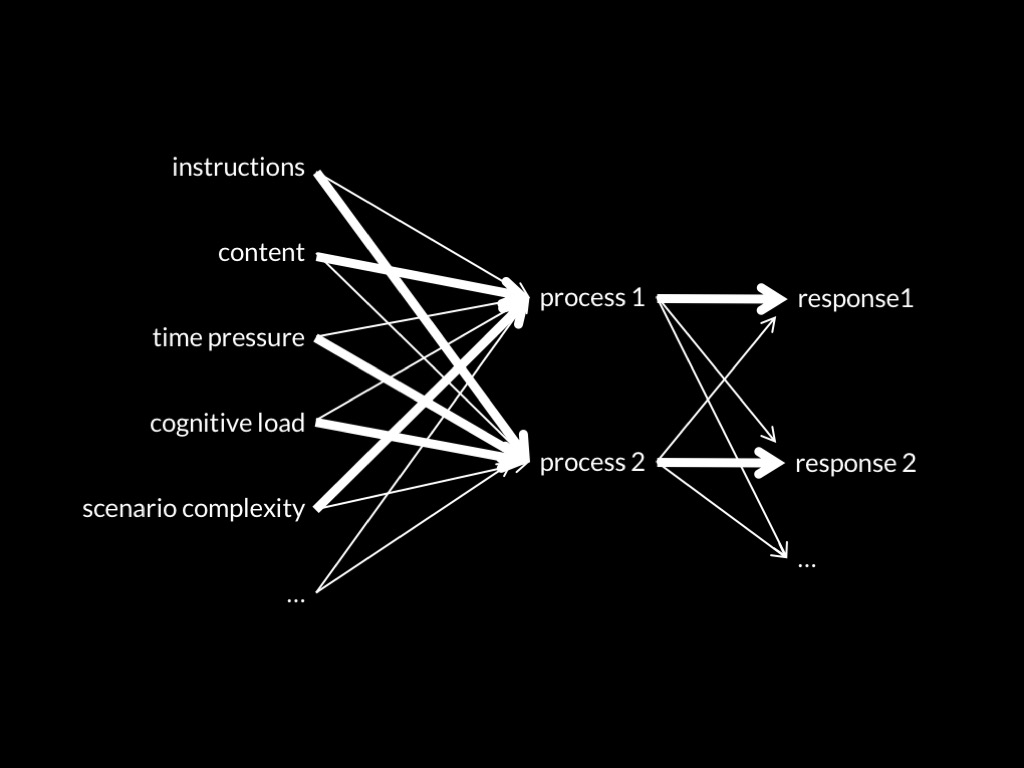

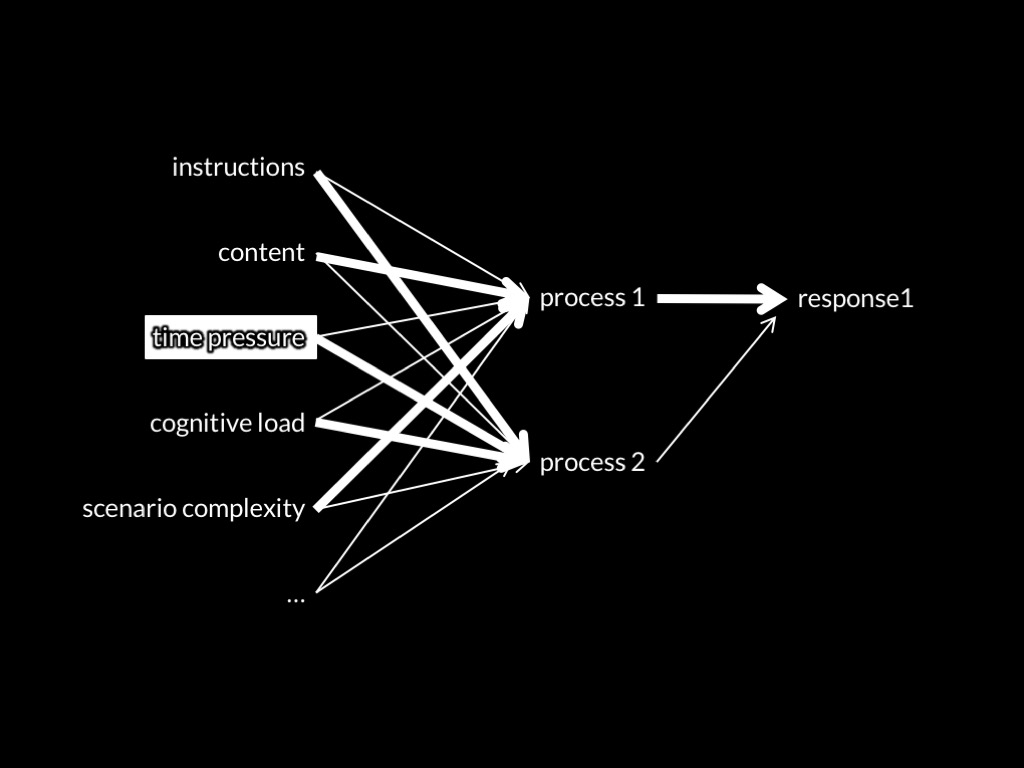

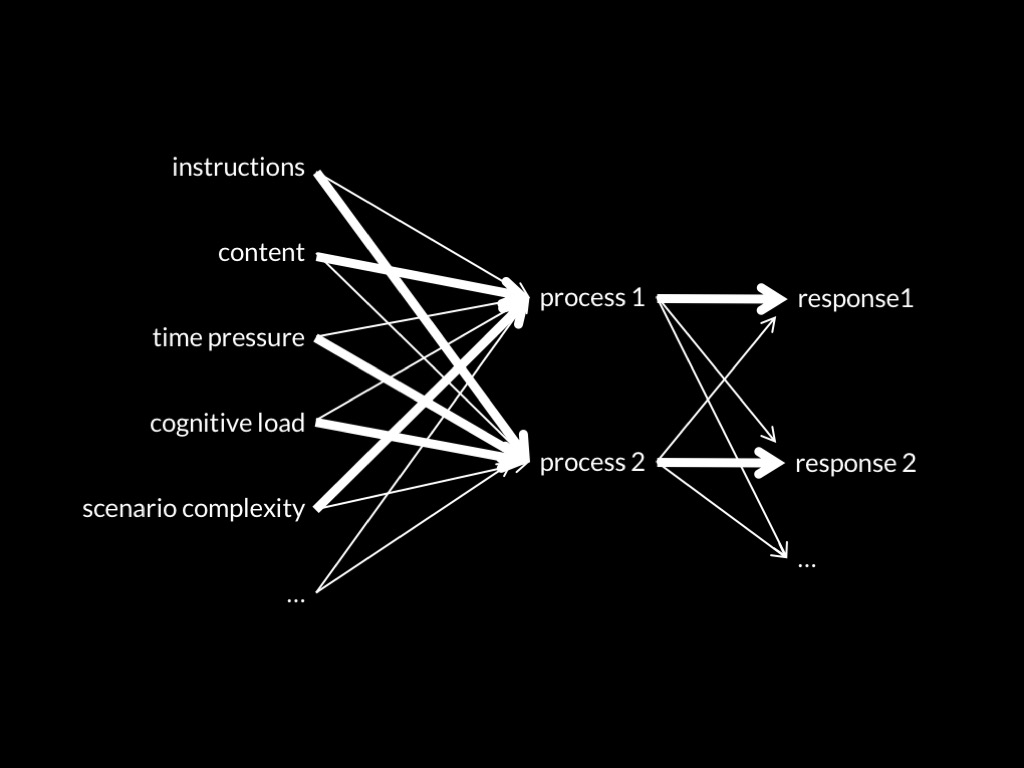

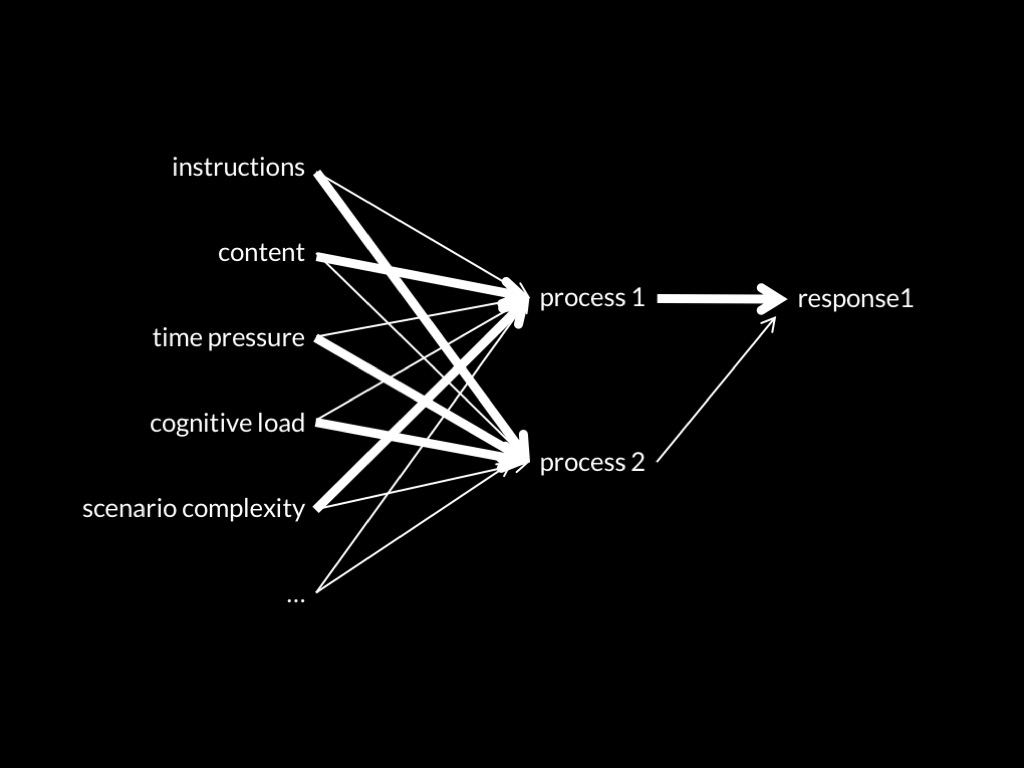

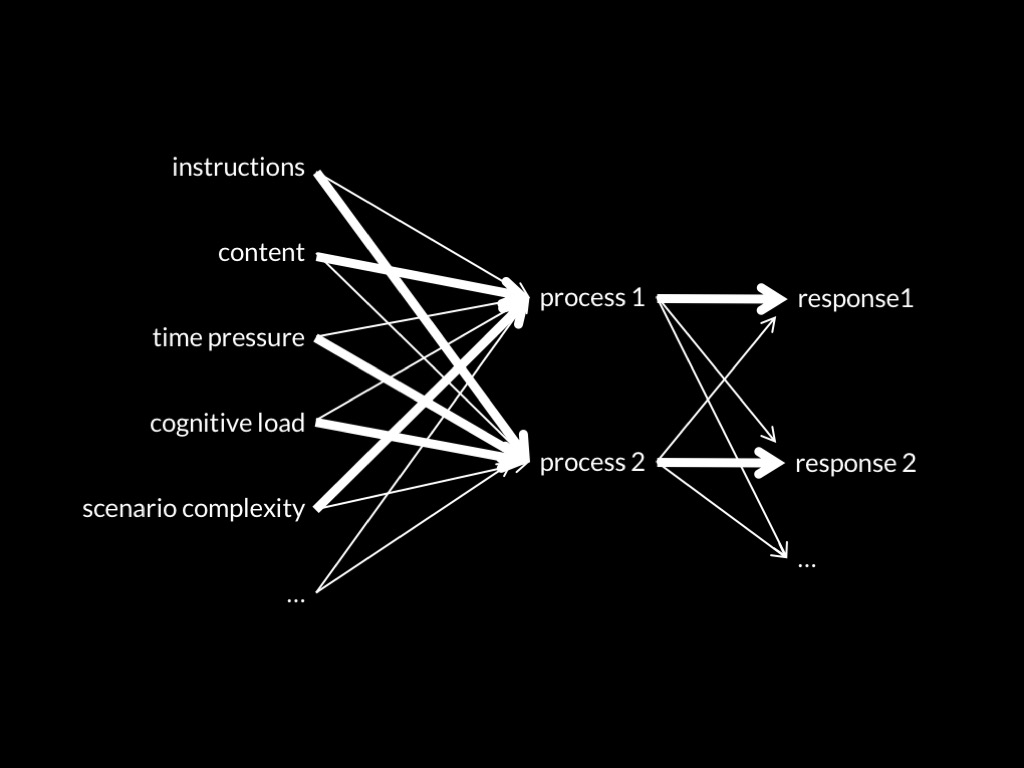

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

Answer the dilemma (see handout)

Terminology

‘consequentialist response’ = yes, kill one of your fellow hostages

Additional assumptions

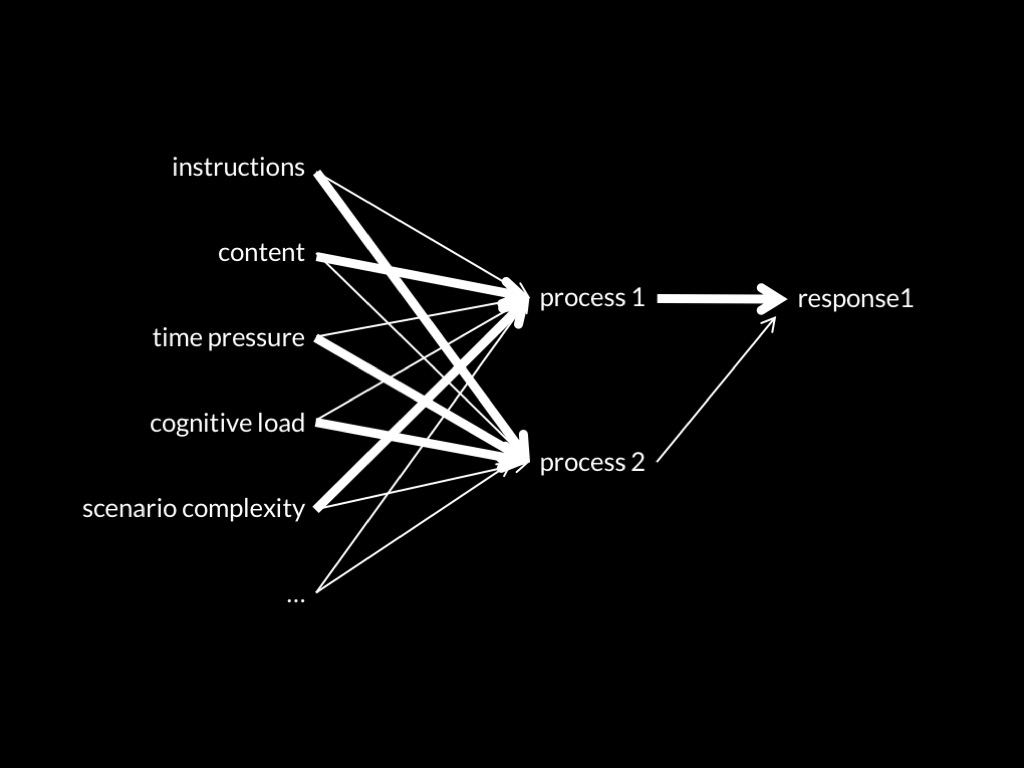

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

The slow process is responsible for consequentialist responses; the fast for other responses.

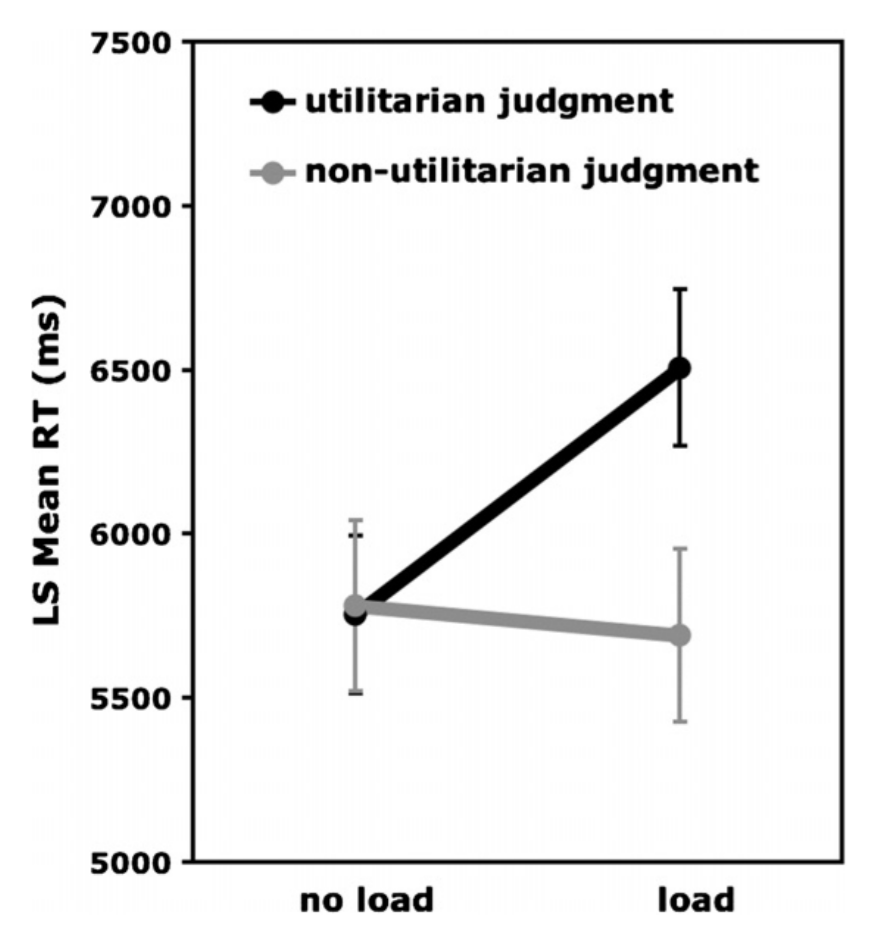

Prediction: Increasing cognitive load will selectively slow consequentialist responses

Greene et al 2008, figure 1

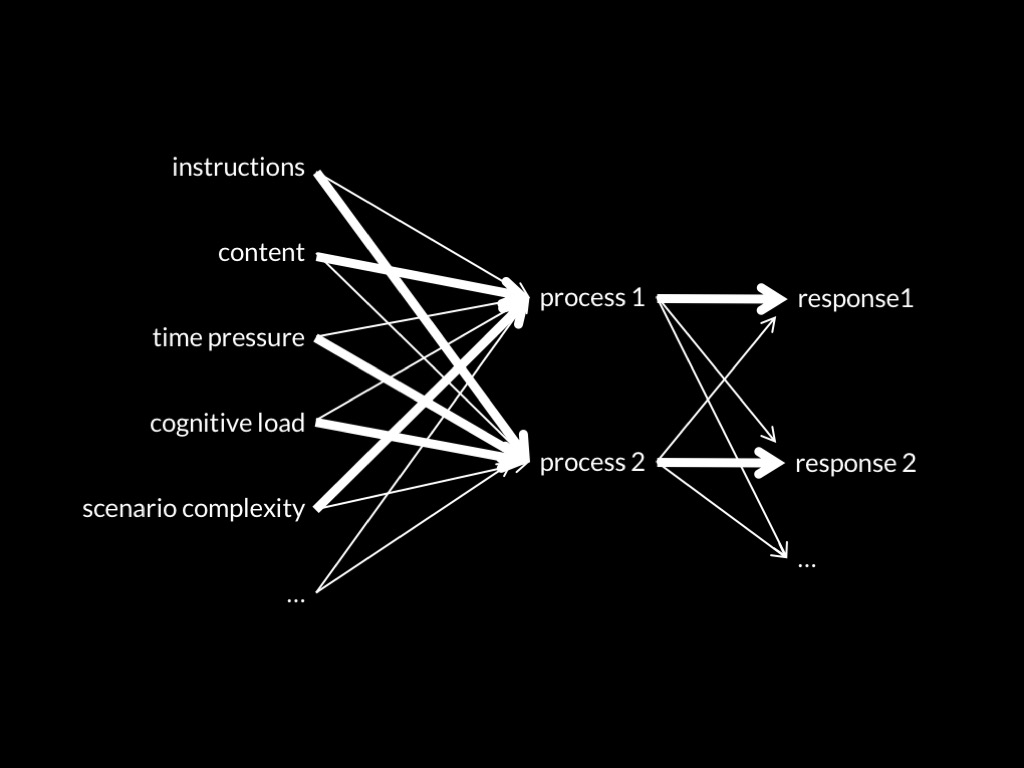

Additional assumptions

One process makes fewer demands on scarce cognitive resources than the other.

(Terminology: fast vs slow)

The slow process is responsible for consequentialist responses; the fast for other responses.

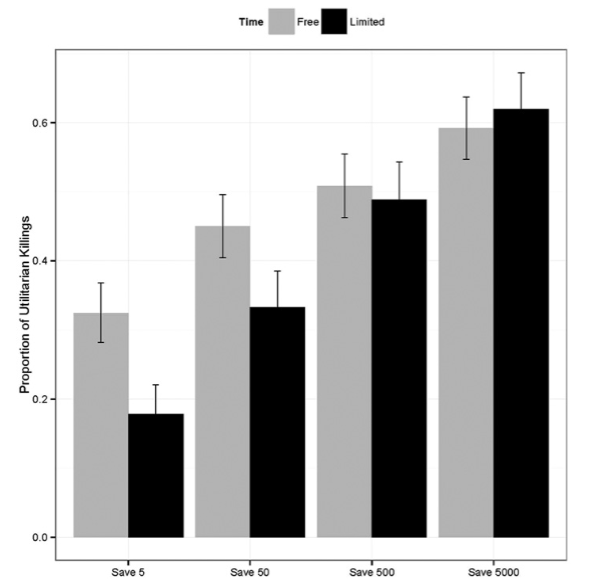

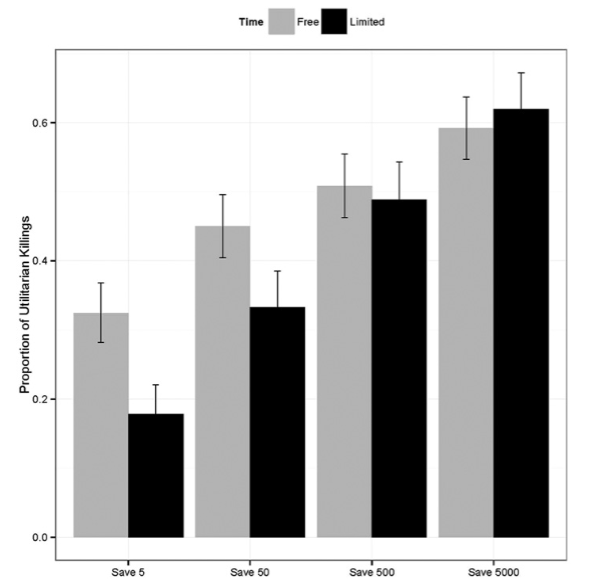

Prediction: Limiting the time available to make a decision will reduce consequentialist responses.

Trémolière and Bonnefon, 2014 figure 4

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

Dual Process Theories Meet the Puzzles

puzzle 1

Why do people tend to respond differently in Trolley and Transplant?

puzzle 2

Why are ethical judgements sometimes, but not always, a consequence of reasoning from known principles?

Dual Process Theory of Ethical Abilities (core part)

Two (or more) ethical processes are distinct:

the conditions which influence whether they occur,

and which outputs they generate,

do not completely overlap.

‘a dual-process approach in which moral judgment is the product of both intuitive and rational psychological processes, and it is the product of what are conventionally thought of as ‘affective’ and ‘cognitive’ mechanisms’

Cushman et al, 2010 p. 48

puzzle 1

Why do people tend to respond differently in Trolley and Transplant?

puzzle 2

Why are ethical judgements sometimes, but not always, a consequence of reasoning from known principles?

Course Structure

Part 1: psychological underpinnings of ethical abilities

Part 2: implications for ethics?

‘Direct Route’

Ought we to condemn incest?

Why do we condemn incest?

Ought we to rely rely on such emotional responses in cases in which there is no special concern about genetic diseases?

Greene, 2014

‘Indirect Route’

‘genetic transmission, cultural transmission, and learning from personal experience [...] are the only mechanisms known to endow [...] automatic [...] processes with the information they need to function well’

Greene 2014, p. 714

unfamiliar* problems = ‘ones with which we have inadequate evolutionary, cultural, or personal experience’

‘it would be a cognitive miracle if we had reliably good moral instincts about unfamiliar* moral problems’

‘The No Cognitive Miracles Principle:

When we are dealing with unfamiliar* moral problems, we ought to rely less on [...] automatic emotional responses and more on [...] conscious, controlled reasoning, lest we bank on cognitive miracles.’

Greene, 2014 p. 715

Trolley

A runaway trolley is about to run over and kill five people. You can hit a switch that will divert the trolley onto a different set of tracks where it will kill only one.

Is it okay to hit the switch?

Transplant

Five people are going to die but you can save them all by cutting up one healthy person and distributing her organs.

Is it ok to cut her up?

‘I strongly suspect that [Transplant] is unfamiliar*, a bizarre case in which an act of personal violence against an innocent person is the one and only way to promote a much greater good.’

Greene, 2014 p. 716

conclusion

cuts

‘In putting forward an account of light, the first point I want to draw to your attention is that it is possible for there to be a difference between the sensation that we have of it, that is, the idea that we form of it in our imagination through the intermediary of our eyes, and what it is in the objects that produces the sensation in us, that is, what it is in the flame or in the Sun that we term ‘light’’

Descartes, The World (AT 3)

sensory perceptions

do not resemble

their causes

But what is moral psychology?

Moral Intuitions and Heuristics: Evaluating the Evidence

replications / related research

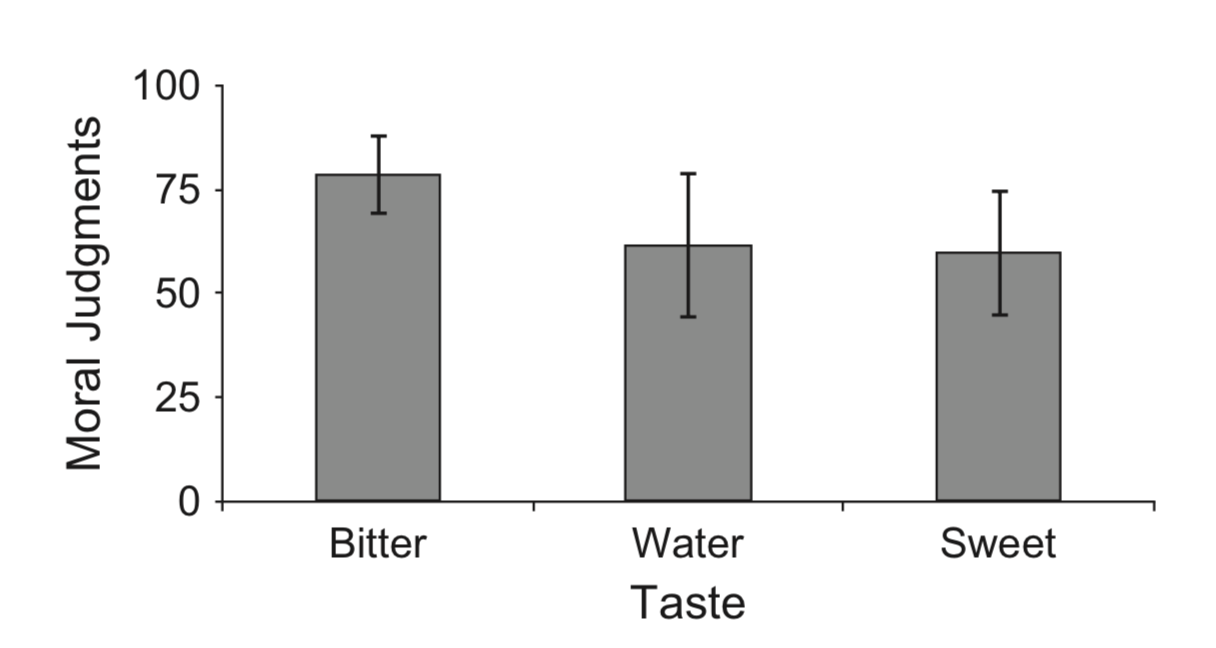

Eskine et al, 2011 figure 1

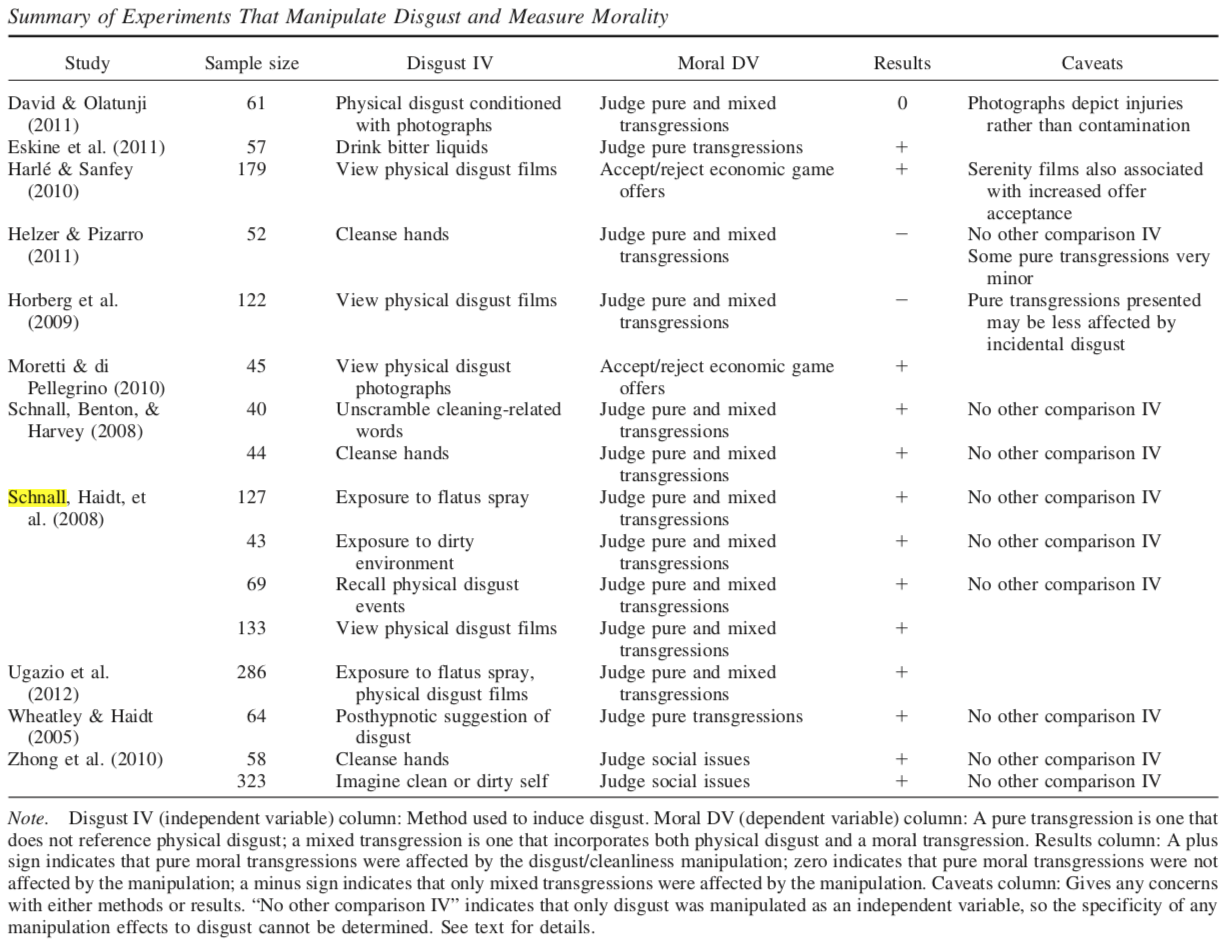

Chapman & Anderson, 2013 table 2

‘To date, almost all of the studies that have manipulated disgust or cleanliness have reported effects on moral judgment. These findings strengthen the case for a causal relationship between disgust and moral judgment, by showing that experimentally evoked disgust---or cleanliness, its opposite---can influence moral cognition’

Chapman & Anderson (2013)

conclusion so far

There seems to be a variety of evidence for the claim

that manipulating disgust-related phenomena

can influence unreflective ethical judgements.

puzzle 1

Why do people tend to respond differently in Trolley and Transplant?

puzzle 2

Why are ethical judgements sometimes, but not always, a consequence of reasoning from known principles?